Week 1

Following the burning of the Yule Log on Christmas Day, on my console table, the New Year begins not with anything new but with the burnt ash of the old year.

For the soon forthcoming book, Rediscovering History in Krems and the Wachau, I embark on the task of copying of the scene of the Temptation shown at the beginning of the Krems Bible and which I stumbled upon in Week 42 of 2024.

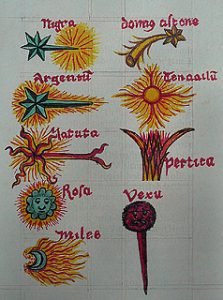

There then follows a copy of Georg Peuerbach’s classification of the different kinds of comet that he had observed. Although depicted as animated and with faces, Peuerbach saw comets as physical entities with predictable orbits that could be calculated and did not see them as portents of the future or indications that divine retribution was at hand.

Last but not least there is a map of the world drawn in 1152 by the Arab geographer, Idrisi, who worked at the Court of Roger II of Scilly. This is significant for Krems as on the map, Krems is one of only three places in Europe that are named, with the other two both being in Italy. Idrisi will have known of Krems from the coins that were minted in the town during the eleventh century.

The Twelve Days of Christmas over, on 6th January, the ashes of the old year are scattered over the beds on all three levels of the garden and on my console table there is but an empty jar.

Week 2

Given The Swerve by Stephen Greenblatt for Christmas, I read of how during the Renaissance, a philosophical poem by a master poet was discovered in a monastery in Germany by an Italian book hunter. The poem is De reum natura and the poet is Lucretius. During the Middle Ages, this work disappeared and was very nearly lost. Following its rediscovery, some fifty manuscripts copies were made with one copy finding its way to Aggsbach Dorf in the Wachau.

Here there was a Charterhouse and in a library catalogue complied during the second half of the 15th century, a manuscript of Lucretius is listed. From my own researches I know that the manuscript is not in the National Library in Vienna. Following the charterhouse’s dissolution at the end of the 18th century, I know that some of the books from the library went to the Abbey of Göttweig that lies across the river from Krems and Sein. Drafting an e-mail, a few days later, I receive the answer that they do not have the copy and furthermore, their helpfully looking in a monastic database on my behalf, has also failed to yield any clues.

In his book, Greenblatt presents Giordano Bruno as if he were an advocate of Lucretius‘ view of the world and of his philosophy. While in some respects these claims can be seen as having some degree of relevance, put the way Greenblatt puts it, this is not correct. As this constitutes a shoring up of the modernist myth described above, it is something I cannot let pass. Greenblatt bases his claims on Bruno’s The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast. This work is particularly significant as it was the book cited by the Inquisition in Rome which led Bruno to the bonfire on which, in 1600, he was burnt. While the passages quoted by Greenblatt are there, what Bruno thereafter says is omitted and so the passages are divorced from their proper context and from Bruno’s ultimate argument. From the rest of what Greenblatt says on Bruno, it becomes clear that, not content with his otherwise immaculate scholarship, he has included Bruno in his book, as he wants at all costs to have a martyr in his story, someone who dies in the name of scientific materialism (as understood by Greenblatt).

Following Copernicus, Bruno believed in a world in which the sun was at the centre of the solar system and not the Earth. Anticipating the main tents of modern materialism, he believed in an infinitely infinite universe which, as it had neither beginning or end, inside or outside, accordingly could not have either the earth or the sun at its centre. Yet Bruno also believed in the objective existence of the countless immaterial relations that pertain between things and in terms of which, in philosophy, the Idea Forms of Plato can be defined. Following on from this, he saw gods and spirits as existing in some way and in The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast points out that the Egyptians and Greeks never worshipped statues as such but rather the ideas and principals that the statues concerned articulated and gave expression to. As Bruno says in The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast:

„Those wise men knew God to be in all things, and Divinity to be latent in Nature, working and glowing differently in different subjects and succeeding through diverse physical forms, in certain arrangements, in making them participants in her, I say, in her being, in her life and intellect; and they therefore, with equally diverse arrangements, used to prepare themselves to receive whatever and as many gifts as they yearned for.“

(translated by Arthur D. Imerti)

Continuing on from this, in other works, Bruno declares himself to be a heroic enthusiast and makes it clear that he saw the Renaissance magnus as, through love and through various techniques, of being capable of ascending up towards the divine aspects of gods and goddesses and from them, on up to the ultimate all all-enclosing One of Being and Truth. This contrasts with the view of Lucretius for whom the gods, if indeed gods there be, are so far away that they cannot possibly be interested in human affairs . Accordingly, if they exist, Lucretius‘ gods cannot be reachable as Bruno not only says but also believed and died for. Despite their sharing a common starting point, Bruno and Lucretius are worlds apart and it is misrepresenting and callous of Greenblatt to stage the death of someone in a way that is at odds with what they stood and died for.

Yet further disappointment lies in store. Although the translation of Bruno’s work is admirable, I am perturbed to find that in a footnote, the translator misrepresents Cusanus in a way that for a serious academic is substandard.

Week 3

As the year enters its third week, I am still adding missing images to Rediscovering History and whilst things invariably fall into place, new questions keep arising and unexpectedly, the chapter on the Krems apothecary, Wolfgang Kappler, proves difficult to beat into shape.

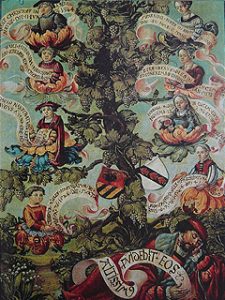

Yet perseverance pays off and reaching out for a book that I bought in Edinburgh over thirty-five years ago, I am rewarded with an insight. This is that a family tree painted on the back of a portrait of Kappler’s wife, was possibly prompted by an image and text from a book by Paracelsus.

In the first instance my case rests on the fact that the painted image is reminiscent of the engraving in the book, with the pose of Kappler sleeping on the ground being a mirror image of that given in Paracelsus‘ book.

This is supported by the fact that Paracelsus was a doctor and alchemist, whilst Kappler was a doctor and apothecary who was interested in alchemy. In both cases, the kind of alchemy that they were interested in was alchemy as a program of bodily and spiritual care and self-improvement. Nevertheless, there are uncertainties concerning the various editions which can only be clarified by looking at the original edition of 1536 and for this I must wait another week. Kapppler’s wife, Madalena, was the mother of thirteen children and as the family tree on the back of her portrait only shows eight of them, it is assumed that the picture was painted in 1544 when the eighth child was born.

This means that only the first edition of Paracelsus‘ Prognostication of the Future over 24 Years could have played a role in the conception and composition of the family tree as the other editions all post date 1544. For introductions and a reproduction of the Prognostication see: https://archive.org. Meanwhile the text accompanying the image resounds with possible echoes of Kappler and what he was trying to do as a doctor and citizen of Krems.

Week 4

From an article written in the 1960’ies, which analyses what was read in Krems during the sixteenth century, I know that books by Paracelsus were in Krems during the period, however I do not know which ones. Returning to the books of protocols in the Krems Town Archive, I follow the page numbers given by the author, only to find that in the wills and testaments, the titles of works mentioned as being by Paracelsus, are not given. Ordering the 1536 edition from the National Library in Vienna, full of expectation I make my way to the capital only to be told that for older works, lending conditions now require written letters of application. Nevertheless the trip is not entirely wasted as along the way, I stop at Kirchberg am Wagram and look at the building where during the second half of the sixteen century, a well-equipped alchemist’s laboratory was in operation. Kappler had connections with the then owner, who moreover died young under mysterious circumstances suggestive that may have died from the poisonous fumes produced in his laboratory. During the seventeenth century, probably at the beginning of the Thirty Years War, the equipment was hidden in an older storage in the vestry of the chapel. Next to the vestry there was a barn where grain was stored, with the roof beams showings signs of smoke, suggesting that this was where the laboratory originally was sited.

Lying asleep on the ground at the base of the growing family tree, in his right hand, Kappler holds a scroll with the statement: „Altissimi pudebit eos“. Asking a friend for help in translating the Latin, we arrive at: „From on high he will put them to shame“. This would seem to refer to Kappler’s having achieved something that his successors with never be able to equal. Looking into the significance of the lily of the valley shown at bottom left of the picture, I learn that although poisonous, the plant contains substances that are of medicinal use and during the Renaissance, a number of authors give recipes for making extracts and distillations.

See: https://digitale-sammlungen.de

Week 5

In Vienna, I confirm that the last image of the 1536 edition is the basis of composition for all later editions and thus possibly of Kappler, as shown in the Kappler family tree. Ordering the manuscript of medicinal recipes that Kappler bought and into which he then wrote commentaries and added recipes his own, search for recipes involving lily of the valley plants. Despite searching for Convallaria majalis, Liliu covallin and „Mayblomen“ this draws a blank. Instead however, I find something else that suggests that the lily of the valley in the family tree is symbolic and stands for Christ as the Salvation of the World and the emblem of new life.