That truth can be a tricky and sometimes dangerous business is proclaimed in a jerky half-catchy tune written by Lyle and Chuck. Played by Warren Betty and Dustin Hoffman, the worst singer-songwriters of all time are the lovable stars of Elaine May’s film, Ishtar, the most expensive comedy of all time. Despite moments of doubt and dissent, the duo’s commitment leads them to a desert kingdom, where succumbing to the allures of Shirra, played by Isabelle Adjani, an ancient map is planted on them and danger lies at every turn. Cluelessly following clues, they purchase a blind camel and trek out into the desert pursued by a host of secret service agents. Surviving a catalogue of dangers, they end up rocking the house in a run-down bar in the capital of Ishtar, with Shirra in the audience weeping at the authenticity of what they have pulled off. In the film, as in philosophy, truth is indeed „a dangerous business“ and there are no short-cuts, only endless meandering’s.

Nevertheless, far from being a case of „Abandon hope all ye who enter here“, in both cases the matter is much more a case of „Welcome to the Labyrinth!“ In the following, starting from an common-sense, analytic account of truth, it is slowly found that behind this, there lies the pragmatic and fractal view of truth that is the corner-stone of One World Pragmatism.

The Adda Seal, a roll seal in the British Museum which in the middle of the composition, shows the winged goddess, Ishtar, who gave her name to the Eaine May film

At first sight a theory known as „the correspondence theory of truth“ appears to satisfy our demands and expectations that in day to day life, there be a way of explaining truth as something that is objective and which exists either „out there“ in an external reality, or in the inner realm of the self in a manner that is somehow analogous to the external form. This was conceived and formulated by the Polish logician Alfred Tarski (1901-1983), who saw that truth was something semantic, which is to say that is something that is applicable to statements and with reference to things can only be used metaphorically. Following Tarski (1956/1983, p. 155):

A true sentence is one which, claiming that a certain state of affairs pertains in some sphere of reality, is true, if the state of affairs of affairs is as claimed and accordingly the associated description is “correct”.

Thus:

„It is snowing“ is a true sentence if and only if, it is snowing.

Here „it is snowing“ functions as a name for what we mean when we say that outside, snow is falling. Alternatively, structural-descriptive names may be used so that the above example becomes:

An expression consisting of three words, of which the first is composed of the two letters I and Te (in that order), the second of the two letters I and Es (in that order), and the third of the seven letters Es, En, O, Double-U, I, En, and Ge (in that order), is a true sentence if and only if it is snowing.

For the Austro-British philosopher, Sir Karl Popper (1902-1994), Tarski’s theory solves a major philosophical problem and clarifies in pragmatic terms what, in day to day life everyday truth „is“ (2002, p. 112 & 163-165). It is, as Tarski saw, a semantic property that strictly speaking, can only be applied to sentences and statements that pertain to refer to states of affairs that can be observed and corroborated by people other than the person making them. Truth is therefore not a property of objects „in themselves“, nor is it something that is purely private and subjective. In discussing Tarski’s theory, Popper stresses the correspondence between the assertion made and the facts to which they are supposed to correspond, more than Tarski does himself. This is because for Popper, Tarski’s theory of truth makes a philosophical point that is of the utmost significance. For any proposition, P, that claims to describe a fact or set of facts in the outside world, there is, if the proposition is true, a correspondence between what P says and the relevant facts pertaining in the outside world that are, in an appropriate sense „P„. As the inverted commas in the first of the examples given above imply and the names of letters given in the second example likewise indicate, the correspondence works via the notion of a meta-language. This enables the status of a proposition made concerning states of affairs in the world to be commentated upon. The meta-language is the framework that surrounds the inverted commas and enables a statement, P, to be talked about as well as the facts pertaining in the world that entail that what P says is to be considered as being „true“. It then becomes possible to say for example:

The statement made in French and consisting of the words „l‘ herbe“, „est“ and „vert“, written in that order, corresponds to the facts if and only if, grass is green.

The phrase „corresponds to the facts“ can then be replaced by the words „is true“, where „is true“ is a meta-linguistic predicate that is applicable to statements. There is thus no recourse to elusive essences which make things true and the sets of circumstances under which the words „l‘ herbe“, „est“ and „vert“ are used does not have to be gone into. If the statement is false, the set of facts attested to are theoretically possible but do not, at the time of claiming, actually exist. The same applies for statements about what a person is thinking or feeling except that the correspondences are more difficult for outsiders to corroborate. This is due to the sets of facts not taking place in the objective world „out there“ but in the private realm of the self. Nevertheless, theoretically at least, the same notion of correspondence is applicable. The correspondence theory is effectively a theory concerned with the agreement — or lack thereof — of conventions with reference to facts. The purpose of the theory is not to assess the appropriateness of a concept’s relation to an external reality that we cannot see. Rather it is concerned with the world of daily experience and what is maintained about it and is necessary for the management of our daily lives. Here truth and falsity arise through our having to confront such things as the fallibility of human memory, the unpredictability of things such as the weather and doubts as to whether someone else is telling the truth or not. In addition, we also discuss complex assessments of a situation, arguing about whether this or that analysis of a situation is best. Often statements are made that refer to the future. As a result of an assessment we may decide to embark on a certain course of action rather than another. Our expectations are then are either fulfilled and become true or else they fail to do so and the assumptions lying behind them are seen as having been false all along only we did not know it. Statements concerning facts in the future are thus similar to statements concerning facts in the present only they cannot be immediately verified. Such day to day situations are all admirably covered by a correspondence theory of truth that pertains to sentences that describe states of affairs in the world and „the facts of the matter“ which are nothing other than the states of affairs in the world which are being referred to. Though when talking about truth we do not use a different language, the context shifts as we cease to talk about facts and speak instead of the truth of statements that describe facts. The facts we talk about are either subjective or objective depending on whether they belong to the social realm of shared life or to the private world of an individual’s inner life. In both cases, the correspondences that take place between the facts and the statements that purport to describe them do so via conventions related to what we mean when, in a sentence such as, „the cat sat on the mat“, we mean when we say „cat“ and „mat“ and „sat“, etc. Such statements make no claims concerning the ultimate realities lying behind the objects under discussion. This is because in dealing with the problems of daily life we are generally not interested in probing ultimate realities. We are simply interested in „getting things done“. To this end we assume that in general the future will be similar to the present.

In any present moment, six kinds of basic, day to day statements can be made. These six different kinds of statement relate to six different kinds of fact. Statements describing Alpha-facts are known as “ostensive statements”. These describe our inner states, that is our thoughts, feelings and sensations, in a way that makes as few assumptions about the external world as possible. They are thus describable as statements taking the form “I am thinking x, or feeling y, or seeing z”. In the case of a statement about what someone else is thinking, or feeling, or perceiving we simply switch the first person pronoun for a third person pronoun or name. The statement then becomes correspondingly hypothetical, as we can never know what another person is subjectively thinking, seeing, or feeling and can only ever make assumptions. In addition to Alpha-facts there are Beta-facts which are simple facts that pertain to the immediate present of the outside world. These can be represented by statements such as “The cat is sitting on the mat” uttered in such a context that the listener can easily, for him or herself, see whether the cat is, in truth, sitting on the mat. Related to these simple facts there are Gamma-facts which though equally simple and straight forward, cannot be immediately verified by the listener and their truth must accordingly be taken on trust. An example of such a fact is the state of affairs referred to when someone says, “My car is parked around the corner”. Though it cannot be immediately verified, the truth content of such a statement can be examined by the listener if he or she is prepared to take the trouble to investigate. Due to the confines of the present, the investigation is however not something that can be conducted immediately. Following on from Gamma-facts, there are Delta-facts which are complex facts expressible by sentences such as “London is in the south-east of England”. This statement can be verified by looking out the window of an aeroplane when flying into London from a known direction. Though this sounds simple, it tacitly assumes a number of things, such as a sense of orientation and knowledge of how cities appear when seen from the air. An alternative approach is to look at a map of Britain. Yet this also entails assumptions, such as the ability to map-read and the reliability of the map being consulted. Abstracting away from immediate realities but very much a part of life there are Epsilon-facts. These are mathematical facts which are so generalised that they are applicable to all manner of objects and situations where there is something that can be differentiated and counted. Through their abstractness, Epsilon-facts are generally accepted as transcending time and of being true in all worlds. If one understands the expression “2 + 2 = 4” then one understands that one pair of objects added to another pair of objects will result in there being four objects. Failure to arrive at this result means nothing other than an inability to implement the rules of mathematics correctly. From these elementary beginnings, the realm of Epsilon-facts extends through all manner of mathematical techniques such as trigonometry and calculus and can be seen as ending with Chaos Theory. Epsilon-facts supply all the techniques of applied mathematics without there being any form of self-questioning about what mathematics is or how it relates to the physical world. Closing the list of facts that are concerned with the immediate present there are Zeta-facts. These go beyond the realm of what is physically verifiable. An example of a Zeta-fact is the statement “London is a city with some 10 million inhabitants” which unless one happens to work in an organisation that is engaged with monitoring and establishing the population of London, must be taken on trust. Summarising, one may say that with respect to any given moment in time there the six basic facts which, taken at face value, do not refer to things that go beyond the moment in question:

Alpha-facts = ostensive facts: “I am thinking x, or feeling y, or seeing z”

Beta-facts = at hand facts: “The cat is sitting on the mat”

Gamma-facts = neighbourhood facts: “My car is parked around the corner”

Delta-facts = complex facts: “London is in the south-east of England”

Epsilon-facts = mathematical facts Everything from “2 + 2 = 4” to Chaos Theory

Zeta-facts = advanced facts “London is a city with some 10 million inhabitants”

Extending beyond the confines of the present there are Eta-facts, which can be characterised by statements phrased so as to contain a prognostication about the future such as the statement “Tomorrow will be a sunny day”. These are not straightforward facts but rather are “would-be-facts”. Eta-facts assume that by and large, tomorrow will be similar to today and that basic phenomenon such as the sunʼs rising and setting will continue to happen just as they always have happened. Although scientists talk of time as a dimension and their equations deal with it as if it were akin to the dimensions of space, for subjects, the dimension of time is fundamentally different to those of space. Where space can be both passively experienced and actively explored, time can only be experienced. We cannot wander through time, strolling about as we wish. Instead, for any given future we must wait for its arrival and once it has past it cannot be revisited. As subjects we are locked in the present and it is through the present that we experience things. In effect the present is the form and format of our experiences. All our memories of the past and all our imaginings of the future are experienced as memories or imaginings in a present from which we can never escape from.

Combining the world of observation and the world of mathematical facts, there are Theta-facts. Theta-facts are the kinds of statements made by scientists. Using Heideggerʼs terminology, the discerning of Theta-facts has vastly increased our ability to “cognitively master” things in the physical world. When referred to, Theta-facts are not always understood. Although many people know what e=mC2 stands for, only a few know how the formular summarises a highly complex apparatus of mathematics. As scientific statements postulate something that lies behind the veil of appearances, they would appear at first sight to fall outwith the scope of a correspondence theory of truth. This is however not the case. Following Popper and the notion of fallibility, an essential part of science is the devising of experiments which have the capacity to show a theory up as false if what it predicts does not come to pass. In the case of theories that are not disproved, a provisional form of correspondence is assumed to hold good, with it being acknowledged that the theory in question may be improved upon and may one day also be disproved. The upshot of this is that whilst it is theoretically possible for a theory to correspond with the way that physical reality behaves, with the correspondence “existing out there”, we are not and never will be in a position to see the correspondence. Accordingly, any theory that is not disproved is granted a provisional status which sets it apart from theories which have been disproved. As Popper says, the search for scientific truth is an ideal, or “regulative principle”. Adherence to this ideal means that scientific truth is striven for, with it being this that leads to scientific theories being continual improved and science remaining in touch with the realities that it seeks to investigate. In this way, scientific theories can be seen as being covered by Tarskiʼs theory of truth in the same way as other statements made in everyday life. Finally there are Iota-facts which are facts concerning life and the universe on their most abstract levels. Among Iota-facts, there are the meta-mathematical facts, theorems and proofs of the mathematical logic on which mathematics is seen as resting. In philosophy, Iota-facts often appear as if abstracted away from almost everything, as a philosopher struggles, within a system of explanation, to find conceptual places for things, processes and aspects of existence that others have ignored and glossed over. While in philosophy there is much discourse and arguing, if one is to maintain some form of realism (regardless of how pragmatic) one must believe that at the end of the day, philosophy does address facets of life and existence that somehow exist “out there”. Summarising again, in addition to the six basic facts that refer to the immediate present, there are three kinds of fact which only have a meaning when from out of the present, a past and a future are projected. These are:

Eta-facts = prognostive facts: “Tomorrow it will rain”

Theta-facts = scientific facts: “E = mC2”

Iota-facts = philosophical & meta-mathematical facts: “Truth is an ideal”, “mathematics is incomplete”

In their spheres of reference, the two lists given above of different kinds of fact, span considerable ranges of complexity. Nevertheless the sentences which describe and refer to them do so, regardless of how complex or simple the sentences and their related facts are, via complex conventions and rules that govern the use of the words and symbols used in their formulation. These often refer, not only to other rules and conventions but to whole chains of procedures, operating manuals and even degree level and post-graduate level courses of study. Statements made concerning the past, point to the past in a way that is similar to the way that statements made concerning the future point to the future. And just as the past can only be remembered and not re-experienced, so the future is not something that can be previewed in ways that have any form of actuality. Rather it can only be imagined via an act of imagining in the present that has no binding reference to the future. In practice statements that refer to the recent past do so in a way that is similar to the statement, “London is a city in the southeast of England with a population of ten million people”. In effect, a past is postulated about which things are said that can be theoretically verified by interviewing people and through the consultation of documents and physical evidence. As the recent past fades, the historical past begins, with documents and written testimonies pointing to that which was but which no one currently alive has actually experienced. As the historical past becomes more distant, history becomes prehistory, with the written sources become ever more scarce and indecipherable until a time comes when there is no writing and the only evidence available are artefacts and archaeological sites. As this point is approached, statements about the past increasingly refer to it through the apparatus of the physical sciences. With the future, the case is similar and the projections with which we are most concerned are those relating to the expected period of time of our own lifetimes. As with the past, scientific models and prognoses of various kinds play an important role.

In clarifying the nature of these various kinds of fact and how the statements that refer to them operate, it becomes clear how Tarskiʼs theory glosses over the holistic complexity by which all propositions, even apparently simple ones, refer to the reality that they address. Given the aims and purpose of the theory, this is perfectly legitimate, however it should not be forgotten that life, language and culture relate to the world that they form, mould and interact with, in a manner that is ultimately holistic. Though scientific statements postulate something that lies behind the veil of appearances and would thus appear to fall out-with the scope of a correspondence theory of truth, correspondence is there as an ideal. Following Popper, via the notion of fallibility, scientific statements can legitimately be said to appear to correspond and to fail to correspond with that which they claim to describe. As it is fallibility that gives scientific theories their claim to objectivity, this implies that the correspondence of a theory to the way that physical reality actually behaves is theoretically possible and „exists out there“ as a correspondence that can be covered by Tarski’s theory, just as in the everyday case (Popper, 1963/1972, p. 116, 229 & 232-235, 1972/1986, p. 314-318 & 319-329). The fallibility of inappropriate theories implies that though we do not see and can never see, positive correspondences, this does not mean that they do not or cannot exist but rather that the search for scientific truth is an ideal, or a „regulative principle“ (Popper, 1963/1972, p. 226 & 229). Adherence to the ideal means that scientific truth is something that is striven for and this leads to the continual improvement of scientific theories, this being indeed what the scientific method is all about.

The conventions surrounding the correspondence of statements about the world to the facts pertaining in the world, combined with the assumption that these states of affairs will persist from one day to the next, form the mindset of daily life. Although we expect the sun to rise everyday, as the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher, David Hume (1711-1776), has shown (1739, 1777) there is absolutely no logical reason or inner necessity that dictates that it will do so. Though the sun’s rising is the result of it following certain laws postulated by scientists, there is no guarantee that stipulates that what these laws say, will always hold true. Hume’s point is that although we detect regularities in nature and evolution has taught us to expect them, there is no underlying logical reason that entails that any regularity observed in the past is of necessity bound to reoccur in the future. All statements that imply or refer to Eta-facts are therefore to be seen as provisional speculations. Accordingly all human knowledge is to be seen as being of a provisional nature. For in the case of Alpha-facts there are a host of implicit assumptions concerning the world and how we see it, all based on a tacit assumption that there is similarity in the world and that this extends both through time and across place. For this reason Popper argues (1972, p. 42-64), that there are no „primary facts“, no „pure sensations“ and no un-interpretated „bedrock of experience“ from out of which our view of the world is learnt by means of empirical observation. Rather we grow up in a world in which assumptions and theories are so inexorably mixed up with our experience of the world that attempts to separate the three is often lead to confusion. Reasoning and assuming things are so much a part of how we experience the world that it is pointless to search for un-interpretated descriptions of what a subject is experiencing just as it is difficult to try and catch oneself experiencing an un-interpretated sensation. Effectively both are generic generalities of which concrete, specific examples, drawn from life are hard to find. Usually when we eat something we nearly always have and idea what it is that we are about to put into our mouths. Generally we simply know whilst in cases where we do not know, such as at a buffet party, we can infer from the context and appearance whether something will be sweet or sour. Thus even here, our taste buds are anticipating something and our expectations erect a framework which begins interpreting and forming the experience even before we have put anything into our mouths. Nevertheless sometimes we are caught out and one could argue that this is about as close to an un-interpreted sensation as one can get. Another way that we can trick ourselves into experiencing something unencumbered with the expectations of our usual perceptions is through experiencing sensations of colour when we are not expecting them. This can be achieved by making a top, one half of which is black the other half of which is white with black, circular lines of varying length (Kelsey in Hendee and Wells, 1993, p. 39-41).

When spun, faint bands of colour will be seen that no camera can capture because the impression is purely subjective. The effect is due to the fact that between the retina and the brain, the transmission and processing times of signals are different for different colours. Though white light appears colourless, it actually contains all colours so that the eye is in fact seeing colour. This is then made manifest through the black half of the disc in combination with the lines on the other side which, exploiting the different processing times of the different colours, exposes them and makes them perceptible. As this experience of colour goes contrary to our expectations it is again relatively un-interpreted. Here too the emphasis is on word „relative“. Despite the fact that they are hard, if not impossible to find, the notion of un-interpretated sensations does have a use as it can help us in clarifying our ideas about knowledge and truth. As part of a discussion and a process the notion leads to understanding.

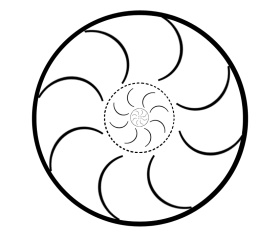

In the case of mathematical and meta-mathematical facts, these are a part of the apparatus via which we perceive the world and so imply that they will be of use in the world of tomorrow. Meanwhile philosophical facts are part of a dialogue concerning our place in the world and how we see things, that changes with time so that the philosophical problems of one age are often very different from the philosophical problems and reflections of another. With the passing of time, some philosophical problems remain, others fade and drift into irrelevance, whilst others still, are solved. One may summarise by saying that all objective knowledge consists of „as if“ formulations that assume that there is similarity in the world that extends both through time and across space. In endeavouring to understand „The Way of the World and the Way Things“, both in science and in daily life, we reach out and try to cognitively grasp things in the world. This invariably means separating the thing concerned from its context and only considering it from our immediate point of view and the current task at hand, so that its place within the whole invariably becomes distorted. Within the world as a whole, truth is thus perpetually by turns hidden and by turns revealed. In the diagram below, a subject at any given point can never see the whole but instead, depending on his or her position within the diagram can only ever see one facet in its entirety or alternatively, has a glimpse into a limited number of facets of the whole, represented by the concave enclaves that represent truth revealed. Seen from another standpoint however, these self-same curved shells hide and shield truth.

Objective truth is always a matter of frames of reference, of parameters and of resolution. Accordingly in the diagram above there is no single point from which a subject has access to all truths — for both the curved nature of the shields and the oversized dot in the middle prevent this. If the oversized dot has been replaced by a modified copy of the whole, the diagram can be given a fractal dimension that reflects the continually shifting boundaries of applicability within which truth both manifests itself and hides itself. This new image not only reflects the fractal nature of reality but also the never-ending task of interpretation that is synonymous both with life and with any scientific endeavour that has not abandoned the ideal of advancing through falsification and of truth as a regulative ideal. The diagram can therefore be seen as an image of subjective thought, forever honing in on contexts of thought and perception and forever stumbling on new recognitions — whilst inevitably overseeing others.

This modified diagram corresponds with what Popper calls „modified essentialism“ — a practical and pragmatic essentialism in which the fundamental properties of the world are, layer by layer (or theory by theory), successively exposed and explored by science and through the sincere practising of the critical, experimental method that is the only benchmark for genuine scientific endeavour (1972/1986, p. 196-197):

… although I do not think that we can ever describe, by our universal laws, an ultimate essence of the world, I do not doubt that we may seek to probe deeper and deeper into the structure of our world or, as we might say, into properties of the world that are more and more essential, or of greater and greater depth.

Continuing he says:

Every time we proceed to explain some conjectural law or theory by a new conjectural theory of a higher degree of universality, we are discovering more about the world, trying to penetrate deeper into its secrets. And every time we succeed in falsifying a theory of this kind, we make a most important discovery. For these falsifications are most important. They teach us the unexpected; and they reassure us that, although our theories are made by ourselves, although they are our own inventions, they are none the less genuine assertions about the world; for they can clash with something we never made.

This fractal view of truth, that nevertheless sees truth as involving some sort of correspondence and thus as an ideal that is to be striven for even though the correspondence imagined can never be seen and a rationally formulated, deterministic, all-embracing account of what there is can never be attained, has much in common with the view of truth articulated by Parmenides. For more on this see the Reloading Humanism Guide to Parmenides, soon to be available as a print on demand book.

The Greek, Pre-Socratic philosopher, Parmenides of Elea

References

Heidegger, M., Parmenides, translated by Schuwer, A., and Rojcewicz, R., Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1992/1998

Hendee, W. R. and Wells, P. N. T. (editors), The Perception of Visual Information, including Detection of Visual Information by Kelsey, C. A., Springer Science and Business Media, New York, 1993

Hume, D., A Treatise of Human Nature, Edinburgh, 1739/Everyman Library by A. D., J. M. Dent & Sons, London/ E. P. Dutton & Co., New York

Hume, D., An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, 1777/The Open Court Publishing Co., Chicago, 1930

Kirk, G. S., Raven, R. E., Schofield, M., The Pre-Socratic Philosophers, A Critical History with a Selection of Texts (second edition), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1983

Popper, Karl R., Conjectures and Refutations, Routeledge and Kegan Paul, London and Henley, 1963/1972

Popper, Karl R., Objective Knowledge, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1972/1986

Popper, Karl R., The World of Parmenides, Routledge, London, 1998/Routeledge Classics, Abingdon, 2012

Popper, Karl R., Autobiography by Karl Popper, in The philosophy of Karl Popper, in The Library of Living Philosophers edited by Schlipp, P. A., Open Court Publishing C., La Salle, 1974/Unended Quest, Routeledge, Abingdon/New York, 2002

Tarski, A., Logic, Semantics, Metamathematics, Papers from 1923 to 1938, translated by Woodger, J, H., Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1956/Hackett Publishing Company, Indiania, 1983