Wine is Everything

Welcome to this Reloading Humanism guide that explains how wine is everything and in wine, there is truth. The tour works through the use of buttons which when pressed initiate a Googe Chrome plug-in that reads the English texts. Once started, pressing the button again stops the reading. Pressing a third time restarts the reading from the beginning. Street directions are therefore at the beginning of each tour item so that the repetition of instructions is straightforward.

THE ORIGINS OF WINE-MAKING

Wine-making can be dated back to the Neolithic. This is a period that began some nine thousand years ago. With the Neolithic, the semi-nomadic hunter-gather groups of the Ice Age became settled. Living in small communities people supported themselves through farming. This brought a new world-view into being, fragments of which can be discerned. Right from the beginning, grapes and wine were integral to the mythology of the new religion. Like most plants in Europe, each winter, the vine dies back and appears as if dead. Then in spring, it puts out new shoots and grows again. By the time summer arrives, it has achieved spectacular growth. The vine was thus seen as a manifestation of a god who embodied the changing seasons. Each year he rose again, as if from the dead.

A GOD OF CHANGING SEASONS

Like the changing seasons, the god of the vine had changing facets and could change form. In spring he was personified as a handsome youth. In Summer, he was the bull of harvest. In the autumn he shrunk to became a mask that was entwined with vines. In this aspect he was the Green Man. This motif that can be found in churches throughout Europe. In European folklore, the green man is equivalent to the Wild Man. In the winter, there was no trace of the handsome youth, the virile bull or of the Green Man. Instead, at the winter solstice a Yule Log would be burnt. Then its ashes would be scattered over the fields. This was so as to ensure that the cycle would start again.

THE GOD OF THE SEASONS AS A BULL

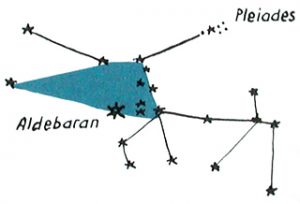

The reason why the god was associated with a bull is written in the stars. During the Neolithic, the constellation of Taurus became visible in the night sky at the beginning of spring. Visible throughout the summer, at the beginning of the harvest season, it would then disappear again. Both in nature and as a personification of summer, the bull represented a peak of strength and virility.

The constellation of Taurus, from The Stars, a new way to see them, H. A. Rey, Boston, 1952

THE GOD OF THE SEASONS AS A GREEN MAN

With the onset of harvest, bulls were sacrificed in thanks and the god of the seasons was prompted to change form yet again. Becoming the Green Man, he represented the autumnal phase of the cycle. This was when the late ripening fruits such as grapes and figs were harvested. Wine was made and in the Middle East, wine was kept in skins made from the hides of bulls.

The Green Man as a vine leaf, detail from the engraved table top of a table from a wine-grower’s cellar, J. Lischka, 1920, Museum Krems. The moto above reads: „God is with us now and forever“

DESICCATION

During autumn, the sap of life and the male forces of nature dried up. Then with the onset of winter proper, the world became cold and frozen. Only when the cold of winter had run its course would the sap return. Then and only then, could the Green Man of vegetation and the Wild Man of rampant growth return.

Relief showing the arms of Dr. Wolfgang Kappler and a wild man, anonymous, Marktgasse 1, Krems, 1532

THE GODDESS BEHIND THE SEASONS

For all his impressive vigour, the god of the seasons was but an aspect of something greater. This was the Alma mater, the great goddess, who was lay behind and embodied all things. Like her male consort, the great goddess was multi-faceted and ever-changing. In human form she was maiden, mature woman and old hag. The maiden represented spring, the mature woman summer, the old woman, autumn. During the winter she withdrew and was an embodiment of death and desiccation. Due to this pattern, the goddess was associated with the moon. The first crescent was analogous to spring, the full moon to summer, the second crescent to autumn. Like winter, the period of withdrawal was associated with the never seen, new moon. The moon’s crescents meanwhile, resembled the horns of the bull, the goddess‘ consort in summer. In this way, the male principle of life was seen as integrated into a more all-encompassing female aspect.

THE GODDESS AS BIRTH-GIVER

That all things were seen was emerging from the goddess is shown by images which show the goddess as a toad. This draws on the similarity between the toad’s natural posture and a woman giving birth in a crouched position. From the Neolithic, this tradion continued on into the Bronze and Iron Ages. An example from Lower Austria gives the form of a toad in three-dimensions. Modeled in clay, when turned over, on the underside there is a low relief depiction of a woman who has just to given birth.

The Lady Toad of Maissau 1,100 BC, Höbarth Collection, Horn

THE GODDESS AND HER MORTAL LOVER

Where the great, all-encompassing goddess could metamorphose from one transition to another, her consort, being subservient, had to die. Reflecting this, in numerous numerous myths tell of a goddess and a mortal lover, who dies in the prime of youth. The great goddess incorporates within herself, the principles of both life and death. Yet her consort knows only life. Accordingly at the end of each life-phase he must be moved on through the holding rituals, rites and sacrifices.

THE GOD OF SPRING

Spring is a time when everything in nature is new and pristine. When this phase passes, spring must make way for the ripening bounty of summer. As today, the arrival of spring was celebrated at Easter. Then at the beginning of May, spring was celebrated again, only this time it was so as to bid him farewell. In Austria, May Day is marked through the erecting of huge poles in the squares of towns and villages. The poles are the trunks of fully grown pine trees. Stripped of their branches and bark, they are topped by a small Christmas tree. Around the pole, may pole dances are performed. Competitions are also held in which young men climb up the pole. In these customs, faint echoes may be seen of rites that celebrate youth and fertility.

THE GODDESS AS MAIDEN

In Austria, the goddess in her youthful aspect is shown by the Sala Women or Saligians. Again referring to newness, the expression means, the glowing, or shinning ones. As presented by later cultures, the Saligans are Wild Women, as they shun the benefits of civilisation. In the woods they protect wild animals and punish hunters who shoot more than necessary. Living by rivers and in woods, they sleep in caves and rocky crevices. When they tire of sleeping on hard surfaces, they enter a human dwelling and sleep on a free bed. As a payment, they leave a lock of hair which can be spun into thread for ever. From high places they sometimes descend and help farmers. Echoing the three-fold nature the goddess from which they derive, the Saligians are thought of as appearing in three’s.

THE GODDESS AS MOTHER

Presenting the goddess as a form of harvest deity is the figure of the Corn Mother. This is an old woman with fiery fingers and breasts that have iron spikes on them. For the farmer, it was essential to leave a last ear of corn standing for her in the field. Another form of the goddess in her last incarnation is Frau Holle, who is an old woman with bad teeth. Known as Hulda or „she who should be honoured“, in Austria, she is also known as Frau Percht. Apart from the corn, Frau Percht is associated with fertility, rebirth and metamorphosis in general. When she shakes her bed, feathers escape. These form clouds that dictate the weather. As the clouds were thought of as being spun, Frau Percht is the goddess of spinning and weaving. She supports those who are industrious and punishes those who are lazy. Frau Percht has a variety of appearances. She can appear as an enormous woman with flaxen hair and a white dress. Alternatively she appears as a withered old woman with an iron nose.

THE LAST VESTIGES OF SPRING AND SUMMER

After the summer harvest, all that remained of the goddess‘ consort were the later ripening fruits of autumn. These included the grapes of the once so vigorous vine. Yet when the grapes are pressed, they immediately start to ferment. Despite being battered and squashed, something in the brew is alive. Then when the juice is drunk, an alien power rises to one’s head. This was seen as a manifestation of the god. Although dead, his spirit was thought of as living on in the wine that had been made from the fruit of his body.

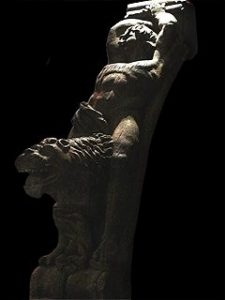

Vineyard spirit carrying the fruits of autumn, Lower Austrian, date unknown, Museum Krems

THE GOD OF THE SEASONS REBORN

For the Ancient Greeks there was no doubt that the intoxicating power of wine was a direct manifestation of the god of the vine. This was Dionysus, whose name means, a burst of light. Dionysus‘ mother’s was Semele, whose name means, earth. The two together thus refer to the fact that the Earth only becomes fruitful when warmed by the light of the sun. Thus both through his attributes and via name, Dionysus is a form of Green Man who once embodied the cycle of the seasons. Meanwhile Dionysus‘ father was the sky-god Zeus, who when on Earth, frequently appeared as a bull.

A mask depicting Dionysus. The mask was originally part of a handle for a large vessel, probably a situla in which wine was mixed. Roman, 1st century AD. Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

THE GOD OF THE SEASONS IN DELPHI

For nine months of the year, the temple at Delphi was sacred to Apollo. Apollo was the god of prophecy and like Dionysus, was associated with light. As the two were half-brothers, from December to February, the temple at Delphi was sacred to Dionysus. Every second year, Athenian women were allowed to leave the confinement of their homes and go to Delphi. This took place in February, with the explicit purpose of honouring Dionysus.

BACCHIC RITES ON MOUNT PARNASSUS

When it came to intoxicants and hallucinogens, and being possessed by their god, the women going to Delphi saw no need to stop at wine. Winter is the mushroom season in Greece. Wandering over the slopes of Mount Parnassus, they found Amanita Muscaria. Eating the red and white mushroom the women had powerful altered states experiences. Calling themselves maenads, they would run wildly over the slopes with their heads thrown back. Apart from hallucinations and senseless abandonment, they experienced upsurges in erotic energy and acquired remarkable strength.

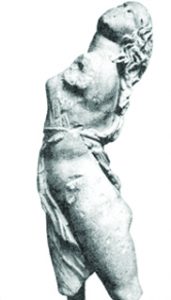

Maenad, 4th C. BC, Collection of Sculptures, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

MAENADS IN THE SNOW

Both written accounts and depictions on pottery show that the women would not balk at handling snakes and fire. They would also tear wild animals to pieces and eat the raw flesh. For a few hours they would rampage over the slopes of Mount Parnassus, possessed by their god. After the wild abandon, they would be found lying exhausted among the snow. Needless to say, the women observed a code of secrecy concerning what they did. Yet to prevent them from dying from hypothermia, they had to be rescued. An eye-witness account says that they would be found lying on the ground, their clothes frozen as stiff as boards. Thus by the time Euripides wrote the Bacchae, everyone knew, or thought they knew, what was being referred to.

Maenad with a snake, detail from a black-figured hydria, the „Eagle Painter“, East Greek, ca 520 BC, Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

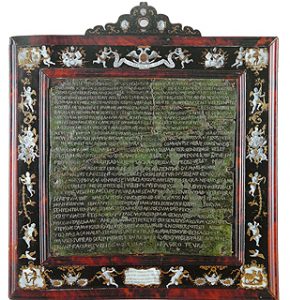

THE BACCHIC RITES IN ITALY

From Greece, the Bacchic cult spread to Italy. The rites were held in secret and often led to excesses. Leaking out, this prompted a series of politically motivated scandals. Political intrigues then led to adherents of the cult being accused of conspiring against the state. After a scandal in Campagnia, the cult and its rites were banned in 186 BC. To this effect the Senate issued a decree. This was publicised through the displaying of bronze plaques in prominent public places. In 1640, one such plaque was found in Calabria. In 1727, it was framed and presented to Emperor Charles VI of Austria.

Plaque announcing Senatus Consultum de Bacchanalibus, Roman Republic, 186 BC, Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

THE COVENANT BETWEEN GOD AND ABRAM

In the Book of Genesis, The Holy Bible, describes how Abram helps a number of kings defeat an alliance of other kings. As he returns, he is met by the Kings of Salem and Sodom. Melchizedek, the King of Salem, is also a High Priest. Bringing bread and wine to Abram, he blesses him. To this effect he says:

Blessed be Abram by God Most High,

Creator of Heaven and Earth.

And praise be to God Most High,

who delivered your enemies into your hand.

Although the King of Sodom offers goods in return for his military services, Abram declines. This is because he has sworn to God, not to take rewards. For rewards would reflect on the king and not upon God. Thereafter Abram has a vision. The Word of God says:

Do not be afraid Abram,

I am your shield,

your very great reward.

God then promises Abram that his descendants will be as numerous as the stars in the sky. This is the first mention in The Bible of wine in a sacred context. Melchizedek’s blessing paves the way for the covenant made by God with Abram.

JESUS AND THE LAST SUPPER

An important part of Christian thinking is the drawing of analogies between the Old Testament and the New Testament. This is because the Old Testament is seen as anticipating and preparing the way for events described in the New Testament. In The Holy Bible, the vine is a symbol for the House of Israel. This was the tribe to which Jesus belonged. In the New Testament, Christ says that he is the true vine and that God the Father, is the wine-grower. At the Last Supper, Christ exhorted his disciples to break bread and drink wine in remembrance of him. This is because he says, the bread is his body, the wine is his blood. Like Melchizedek, Jesus was using the bread and the wine as something that pointed to a covenat. This was the doctrine of the remission of sins drawn up by God and sealed by Christ through his suffering and death.

CHRISTIANITY AND THE GOD OF THE SEASONS

In both the Neolithic tradition and the Christian tradition, the vine is a personification of a figure who was destined die. Conquering death, both Jesus and the god of the seasons, rise again. It was therefore easy for Christian missionaries to argue that Christ was a new form of this older concept. Missionaries and priests were thus allowed to hold Christian services at pagan temples. This they did with the idea of subverting the old religion, subtly steering it towards Christianity. The problem was that the old ways were not so easily eradicated. For hundreds of years, the two traditions existed side by side and in varying forms of fusion. Over time, this appears to suited not only local populations but also local priests.

Reflecting the fusion of the old religion with the new, depictions of vines occur in churches throughout Europe. Green Men and other clearly non-Christian motifs also abound. This is not only true of early Romanesque churches but also of much later Medieval churches. Examples may even be found that date from the sixteenth century. A Romanesque example is on display in the cellars of Museum Krems. This shows the goddess of the Neolithic as a harpy in her death aspect.

Harpy, Early Christian Age, Museum Krems

THE GODDESS RELIGION AND THE CHURCH

Although local priests were not opposed to the fusing of Neolithic and Christian traditions, Church Bishops did not approve. In letters, Bishops repeatedly urged local priests to ban pagan activities from being held on church ground. In some countries these bans were effective. In others they were ineffective. During the Renaissance, there are reports of people dancing in churches during sermons. The inability of the Catholic Church to stamp out dancing in churches was one of the complaints brought by Luther. With the Counter-Reformation however, appropriate measures were taken. The result was that in both Protestant and Catholic countries, dancing and the holding of fairs on church ground was eradicated.

THE SUBVERTED RITES OF FRAU PERCHT

With the Reformation and Counter Reformation, throughout Europe, pagan traditions that were not banned were secularised. An Austrian example of a custom that survived through being subverted, is Perchten Running. This is held at the beginning of December. The purpose of this practice appears to have been to emphasise the withdrawal and seclusion that the approaching winter solstice demanded. The rites involve young men dressing up as demons. Clad in furs and wearing grotesque masks with large horns, they yield whips and shake chains. With the Counter Reformation, this practice was turned back on itself. Instead of honouring Frau Percht and her withdrawal to the sacred space of a church, she was expelled from it. The goddess expelled, the rite then became one in which women and girls who dared to go out, were chased through the streets. In modified form, Perchten Running may still be seen today.

THE HOLY COMMUNION OF CHRISTIANITY

At the Christian ceremony known as Holy Communion, the communion referred to is a communion with God. Via the bread and wine which were used as sacraments, this recalls the covenant made between God and Abram. Following what Christ said at the Last Supper, the bread stands for the body of Christ, the wine for his blood. After a ceremony, believers eat a small piece of the consecrated bread and drink a sip of the consecrated wine. For Protestants, the bread and the wine are merely symbols. For Catholics however, a miracle has taken place. The bread and wine are not symbols but have been literally transformed into the body and blood of Christ. Yet seeing an analogy between Christ’s genealogy and Passion, and the vine and its fruit, offers another way of viewing the matter. As the new Green Man, Christ is the vine and is associated with wine-making. If one accepts the analogy, the link being literal and there is no need for any form of transformation. Yet thinking and seeing things in terms of analogies is alien to the modern mind-set. This means that the matter becomes polarised into a question of, miracle or symbol? Nevertheless, during the Middle Ages, among the illiterate, seeing the world in terms of analogies is likely have to have been predominant. This is suggested by the attention given in art to the stations of the cross.

Christ carry the Cross, Stations of the Cross, Piarist Church, anonymous, 1658, Krems

THE PASSION OF CHRIST AND WINE-MAKING

Once picked, the grapes were placed in tall, narrow containers where they were bashed with thick poles. Then they were shovelled into a barrel. This was mounted on a cart so that the must could be carried down for a second, more thorough pressing. The reason for the initial battering was to save space. The battering and the journey in the cart were analogous to the torture and mockery that Christ went thorough prior to being crucified.

The Flagellation of Christ from the Aggsbach Altarpiece, Jörg Breu the Elder, 1501. The altarpiece was painted for the Charthouse at Aggsbach. This was dissolved in 1782 and the altarpiece is now in the Augustine Monastery at Herzogenburg

THE CRUCIFIXION, THE BURIAL AND WINE-MAKING

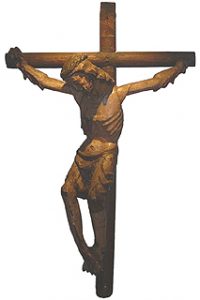

Thereafter, where the pressing of the grapes was the crucifixion, the storing of wine in a cellar, was his Christ’s burial. During the Middle Ages, these parallels lead to the notion of Christ as „the Man of Sorrows“. This made human beings were nothing but mean, wretched sinners. The despicableness of human nature was such that it was not enough for God to sacrifice his only son. The son had to undergo a programme of mockery, torture and humiliation as well. Simply by virtue of being human, human beings were inherently wretched and sinful. Exemplifying this conception, a half-size crucifix in Museum Krems shows Christ hanging from the cross. Emaciated and exhausted, from the Saviour’s wounds, blood flows in hyper-real, three dimensional forms.

Crucifix, mid 14th century, Museum Krems

A BACCHIC FORMULAR

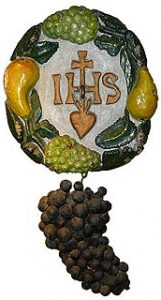

Shying away from the analogies that can be drawn between the effects of wine and Christ’s rising from the dead, the Church did use the letters, I, H, S. This was a formula used by the followers of Bacchus in Italy. These stood for, in hic salus or in hic signo, both of which mean, in this sign. Unfortunately it is not known what sign or object the expression refers to. It be the staff borne by Bacchus and his followers. This consists of a long stalk of fennel, topped by a large pine cone. The significance of this is that stalks of fennel were used by Greek apothecaries for storing drugs. Later the letters I, H, S, were interpreted as standing for, Iesus hominum salvator. This means, Jesus the Saviour of Man. Cut free from their previous sphere of meaning, the letters may be found in churches and paintings the world over.

Insignia of the Wine-Growers‘ Guild, 1739, Museum Krems

THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD

Following an age-old system of identifications, the Church equated all that was good, true and beautiful with light. Darkness was demonised and stood for all that was bad and corrupted. This was meant that Christ, as the conqueror of darkness, was analogous to and so was, the sun. He thus became the Light of the World. Meanwhile his mother, the Virgin Mary, became Queen of Heaven. Born on the day of the winter solstice, Christ was the conqueror of darkness and evil.

Jesus receiving Mary as Queen of Heaven, Joseph Matthias Goetz, Parish Church of Saint Vitus, 1732-1736, Krems

A NEW VISION OF HUMANITY 1

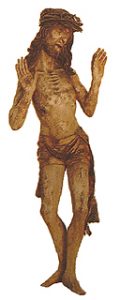

With the Renaissance, the ways in which past events were seen as prefiguring New Testament events were extended. Via the equation that linked Christ with light, Jesus was seen as being prefigured by the half-brothers, Apollo and Dionysus. Meanwhile, God the Father was seen as being anticipated by the fatherly figure of Zeus. In this way, scholars and theologians lessened the emphasis on sin that had characterised the Middle Ages. No loner inherently wicked, a new view of humanity was ushered in. Reaching up towards the light, people were accorded the ability to do good and to perform noble deeds. This can be seen when two Renaissance sculptures in Museum Krems are compared with the crucifixion image already encountered. These show Christ very much alive, standing on his own two feet and showing his wounds. Though the wounds are clearly depicted, the poses show no signs of pain or suffering. In the first example, the message is: It was for you that I allowed them to do this to me. Look, believe and I shall absolve you from sin.

Christ Arisen, anonymous, around 1470, Museum Krems

A NEW VISION OF HUMANITY 2

Where the first figure of Christ Arisen is addressing us, the second is caught in an act remembering the torment and seems to be saying, Yes, it was out of love for you that I did this.

Christ Arisen, anonymous, around 1480, Museum Krems

FORGIVENESS IN DÜRNSTEIN ABBEY

In the Festive Hall of Dürnstein Abbey, a fresco on the ceiling shows a scene from the New Testament. This is an incident told in Luke, in which Jesus was invited to share a meal with a Pharisee. Seeing Jesus enter the building, a woman followed him. When he had taken his seat, she presented him with an alabaster jar filled with ointment. Then she broke down in tears. Using the water of her tears, she washed Jesus‘ feet. Afterwards she dried them with her hair and kissed them.

The host saw that the woman was a prostitute. If Jesus was a prophet he wondered, why would he let a prostitute touch him? Overhearing the aside, Jesus asked him a question. There are two debtors, One owes a lot of money, the other only a small sum. If the creditor cancels both debts, which of the two would be more grateful? To this the Pharisee replied that the one with the greater debt would be more grateful. You are right, Jesus said. He then pointed out that when he arrived, no one had given him water to bathe his feet. No one had kissed him. No one had anointed him with oil. The woman’s sins were many, Jesus admitted. Nevertheless she was repentant and he accordingly declared her sins forgiven.

At this, the Pharisees began to mumble discontentedly among themselves. Who is this who dares to declare such sins forgiven? The Festive Hall was where the Provost of Dürnstein Abbey, Hieronymus Übelbacher, would receive important guests. The fresco sets the tone for how Übelbacher saw his role as host. Overriding all else, the best reason for any celebration, was God’s love of the world. Out of this, he sent his only son to die. By conquering death and rising again, Christ was able to absolve humankind kind from sin. In any coming together, the most important thing was penitence and to forgive as God forgives us.

Jesus, the Harlot and the Pharisee, Martin Johann Schmidt, 1775, Festive Hall, Dürnstein Abbey

WINE IS EVERYTHING

Alluding to the theme of forgiveness announced on the ceiling of the Festive Hall in Dürnsten Abbey, is a building just outside the town. If at Dürnstein, one looks from the Steiner Tor to the north-east, a yellow and white building stands out. This was built by Übelbacher as a Lustschlossl, or palace for the appetites. Inside a motto proclaims, Wine is everything. Even more confidently, another proclaims:

Wine is over and above everything.

These mottoes refer to two things. On the one hand, they refer to the role of wine in the Christian Sacraments. On the other, they refer to Übelbacher’s joie de vivre. Well-earned and in their right place, the joys of man do contribute to the joy of God. Seeing life as nothing but a test that decides whether one goes to Heaven or to Hell, belies the beauty and complexity of God’s creation. It is thus our duty to graciously accept the joys of life and give thanks for them, by appreciating them. The relevance of this is that it was in the Lustschlossl that Übelbacher entertained his friends. Reading between the lines of his diaries, it is clear that on occasion, Übelbacher and his friends lived it up. The fresco in the Festive Room of the Abbey and the two mottoes, both point to something. This is doctrine of the forgiveness of sins with which all iniquity is washed away. Christ is the wine that washes away sin, yet wine is also that helps us celebrate the joys of life, as God the Father intended.

The Lustschlossl built by Hieronymus Übelbacher at Dürnstein

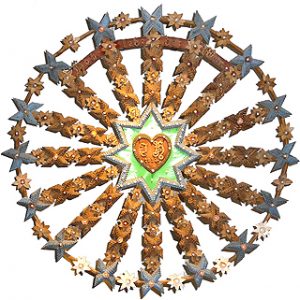

GUARDIAN STARS

From the end of August until the middle of November, wine gardens were closed to public access. This was to prevent unlawful picking. During the period of ripening, guards lived among the vineyards in huts which still dot the landscape today. To show that the vineyards were closed, long poles topped by stars were erected and adorned with bunches of thistles. The first mention of such a pole being erected in the Wachau, dates from 1394. Made of strips of wood, these „Hütersterne“ are composed of dozens of Saint Andrew’s crosses arranged either in a radial fashion or in concentric rings. The stars, recall the wandering star that in The Bible, the three wise men followed. Arriving at Bethlehem, it stood still over as an announcement of Christ’s birth.

Hüterstern or guardian’s star, 1913, Museum Krems

WINE-GROWERS AND THEIR SAINTS

The wine-growers had a number of patron saints. These included the Virgin Mary and Saint Paul. Two saints were however unique to wine-growers. These were Saint Urban and Saint Martin. Saint Urban died a martyr’s death in 230. As Bishop of Langres he is credited with bringing the cultivation of the vine to his diocese. At some stage he evaded persecution by hiding under the leaves of a vine. This was possible as up until the nineteenth century, vines were planted to grow up and around poles. The poles stood alone and the climbing vines formed bushy outcrops. Under the vigorous growth, there was space enough for fugitives to hide. As Saint Urban was compelled to hide, not for days but for weeks, he fed himself on grapes. The vine thus gave him both camouflage and sustenance.

Where Saint Urban was responsible for wine-making in general, Saint Martin was specifically concerned with the fermenting and ageing of the wine. Evidently an imposing personage, he was invited to dine with the Roman emperor, Maximus. On this occasion, he was accorded the honour of being allowed to take the first sip of wine. Out of this, there arose the belief that after pressing, it was Saint Martin was who oversaw the wine’s subsequent transitions.

Saint Martin (right) and Saint Urban (left), detail from a relief carved on the end of a barrel, 1857, Museum Krems

THE DAY OF SAINT MARTIN

In Austria, the still fermenting wine is known as sturm. Murky, cloudy and sweet, it can be sampled in vineyard taverns in October. After ten days, the yeast settles and the still dusty wine is tasted. Pumped out into fresh barrels, the wine is known as young wine. From this moment on, the barrels must be kept full so as to prevent oxygen from spoiling the wine. The 11th November is Saint Martin’s Day. On this day the new wine was traditionally christened and officially presented. On Saint Martin’s day, goose is eaten.

Figure of a youth riding on the back of a lion representing the young wine, wine-press support, Ladendorf, 17th C., Museum Krems

NOAH AND WINE-MAKING

In a secular context, wine appears early on in The Bible. First mentioned soon after the Flood, The Bible says that Noah became a man of the soil and planted a vineyard. Following in Noah’s footsteps, wine-growers clearly played a part in the Christian story. Yet as lay people, they knew it was not their place to claim too much of a central role. Accordingly they associated themselves with Noah. This enabled them to be close to the central mystery without making any undue claims. In Lower Austrian folk art, Noah is often shown together with a goat. This is because The Bible gives no explanation of how the Patriarch came to invent wine. Regional tradition filling in, the saying is that it was a nibbling goat that prompted him to try the unknown fruit. After harvesting a sample of grapes in a pot, Noah was then distracted. By the time he returned, the grapes were fermenting. Yet undaunted, he drank the brew. As The Bible then says, overindulging as, the Patriarch became inebriated and fell asleep. Later, he was found lying naked on the ground and was discretely covered by his sons.

Noah and the goat, detail from a relief carved on the end of a barrel, 1881, Museum Krems

THE SCOUTS OF ISRAEL RETURN

In the Old Testament another reference to grapes occurs in Numbers, 13:23. Arriving in the Promised Land, God instructs Moses to send out scouts. As a proof of the land’s bounty, the scouts return with a bunch of grapes. The bunch is so huge that it is hung over a pole and carried on the shoulders of two men. As shown carved on the end of a barrel in Museum Krems, a text accompanies the scene. This hints at the problems encountered by Noah when he first sampled wine. Translated, it reads:

The scouts have brought

the wine home

and for sure the monkey

won’t be far away.

This is a reference to a Jewish interpolation to the story of Noah.

The scouts of Israel returning with grapes, detail from a relief carved on the end of a 1,890 Litre barrel, Museum Krems

NOAH IN THE MIDRASCH TANHUMA

In the Midrasch Tanhuma, the Devil sees Noah planting up his vineyard. Going over to him, he asks what he is doing. Noah replies that he is planting out vines on which a sweet fruit will grow. Hearing this, the Devil suggests that they enter into a partnership. For his part, the Devil promises to make a sacrifice that will double the yield. Once harvested they can then divide the grapes equally between them. To this, Noah agrees and the Devil duly sacrifices a sheep, a lion, a pig and a monkey. These he buries in the soil that Noah has planted up. The Devil then says that the juice of the fruit will make whoever drinks of it mild like a sheep. If more is drunk, the person will acquire the courage of a lion. Yet continued, over-indulgence will make them behave objectionably like a pig. Thereafter, whoever continues over-indulging, will behave like a monkey. To the believer who drinks wine, Christ offers joy and forgiveness. For non-believers, the Devil holds up a mirror that peers ever more deeply into the murky depths of the human soul. For both believers and non-believers alike, there is truth in wine and in many senses, wine really is everything.

END OF „WINE IS EVERYTHING“

Krems Tour: Trade and Prosperity, Heresy and Belief

Welcome to this Reloading Humanism tour of Krems. The tour works through the use of buttons which when pressed initiate a Google Chrome plug-in. This reads the English texts. Once started pressing the button again stops the reading. Pressing a third time restarts the reading from the beginning. Street directions are at the beginning of each tour item so as to facilitate the repetition of instructions.

To begin the tour go to Körnermarkt 14. Entering Museum Krems say that you wish to see the model of the town, which is located in Room 2 and for which there is no entry fee.

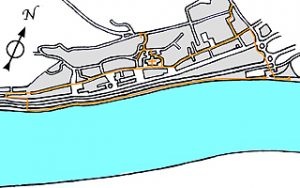

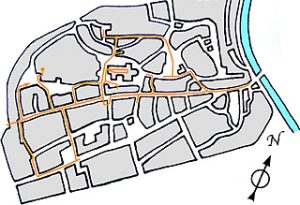

MUSEUM KREMS: MODEL OF THE TOWN

The model shows the town as it would have looked between 1760-1795. The main features of the town such as city-walls, streets and churches were established by the fourteenth century. The first settlement was built on a rocky outcrop that overlooked a wet-land landscape. This was caused by the meandering Danube. On the model, the site of this first settlement can be seen above the town’s eastern gate. Here there was a pallas or stockade where refuge could be sought in times of danger. To the North-West, the trapezoid square with three trees and a covered well in the middle, was where markets were held. This is the Hohe Markt or Upper Market. In due course the stockade was rendered superfluous by the building of a castle. This was situated on the South side of the Upper Market. In the thirteenth century, the castle was transformed into a town palace, identifiable on the model by its castellation’s.

The settlement was first mentioned in 995 in a document drawn up after the Battle of Lechfeld. This battle was fought near Augsburg in Germany. At the battle, a marauding army of Magyars from Hungry were defeated. Following this decisive victory, the soon to be Holy Roman Emperor, Otto III, initiated a program of colonisation. Following this program the unsettled and uncultivated lands of the Wachau were given to monasteries in Southern Germany. The monks quickly realised that the slopes of the valley were ideal for growing wine. Large areas of the Wachau and the area around Krems were transformed into a patchworks of vineyards owned by different monastic institutions. In this way, craftsmen and traders were attracted and slowly, law abiding communities were established.

MUSEUM KREMS: SAINT VITUS

By 1014, Krems had grown to such an extent that land was granted to the parish church. This was so that a larger building might be built. Situated immediately below the original church, it was not until a century later that the new church was completed. Built as a Roman basilica, the new church was dedicated to Saint Vitus and was linked with the old church by stairways. Saint Vitus was the patron saint of apothecaries and dancers and was invoked in cases of epilepsy. In Room 2, a sculpture dating to around 1520 shows him in a vat with his hands clasped together in prayer. Vitus was martyred as a young man by being placed in a vat of boiling oil. Praying that he might withstand the torment to come, he was lifted up to heaven by a swarm of angels.

MUSEUM KREMS: COINS

Between 1120 and 1194, coins were minted in one of the castle towers. In Room 2, examples of these Kremser Pfennige or Krems Pennies are on display. The reverse of the coins often features a walled city with gates. The existence of a city-wall with gateways in Krems is attested to in documents that date from 1188 and 1193. The town depicted on the coins can thus be assumed to be Krems itself. Meanwhile the obverse often shows a figure holding two lions by their tails. Alternatrively the figure is in combat with a lion. Krems or Garmisia was the only European settlement outside Italy that the Arab geographer, Idrisi gave a name to on his map of the world of 1153. This was a result of the Krems Pennies being used as currency abroad. In 1196, Krems was important enough to be made a judicial seat. In Room 2 there is a cupboard where the town’s judicial documents were kept. Also on display are a judge’s sword and sceptre which were symbols of office.

THE FOUNDATION OF THE DOMINICAN MONASTERY

Leave Museum Krems and walk South past the golden rain tree. Cross the square at its narrowest point. Then turn around to look back at the Dominican Church. During the Middle Ages schools and teaching slowly became established. This resulted in boys being taught by monks at grammar schools. With education people began to think for themselves and questioned Church doctrine. This resulted in heresy. The most well-known heretics of the Middle Ages are the Cathars. For the Cathars, there were two gods one good and one evil. The evil god was the creator of matter and was the god of the Old Testament. The good god was the creator of spirit and was the god of the New Testament. Cathars believed that human beings were sexless spirits caught in the material realm of the evil god. Cathars sought to escape perpetual reincarnation in the material world, by returning to the good god of the New Testament. To counter the danger of schism that these and other beliefs brought, the Order of Dominican Friars was founded in 1216. In 1238, Dominican monks from Hungry were summoned to fight the heresy which had broken out in Krems. In 1240 work started on the building of a monastery. As there was not enough space inside the town, the monastery was situated outside the city walls. Unlike the other religious orders, the Dominicans wanted to be close to the people whose souls they wanted to save. After twenty years the church was completed in 1260. It is assumed that the rest of the monastery was also finished at this time. In 1315 an inquisition identified sixteen people in Krems who denied essential aspects of the Catholic faith. In the report the heretics were recorded as doubting the authority of the Church and its priests. Burnt at the stake, the heretics were not without sympathisers for a Dominican Friar, was sized by a mob and killed with a sword. Buried in a stone coffin in the Dominican Chruch Father Arnold’s body was exhumed in 1639. Examination of his bones revealed sword wounds to the head and upper arm. Whether those burnt were Cathars or Waldensers is unknown. Less radical, Waldensers questioned whether Church officials were qualified to preach the Word of God. They also rejected the cult of relics and Holy Water. For a Waldenser it was irrelevant whether a person prayed in a barn or in a church. Refusing to recognise the authority of the Pope, Waldensers are seen as precursors of the Reformation. Sometime before 1330, the small apse of the Dominican Church was knocked down and replaced with a larger structure. Still standing today, this is decorated in a High Gothic style.

OBERE LANDSTRASSE 1

From opposite the Church, follow the Gaheisgasse down to the Obere Landstrasse. In Krems, the beginning of the thirteenth century brought a second phase of expansion. From the South of the rocky outcrop, the town spread out towards the West. During this phase the old high street, the Untere Landstrasse, was extended westwards to form the Obere Landstrasse where you now are.

At the Obere Landstrasse, turn left and then immediately right. Proceeding along the Sparkassengasse leads to Hafnerplatz. At the southern end of the square, there are two Medieval buildings. The left-hand building was a chapel and was built in around 1250 as part of a defensive complex. This complex was designed to guard the town’s south-western corner. The outer walls and a defensive structure known as a pallas are around the corner from the chapel. During the fourteenth century, the area to the north-west of Hafner Platz was partially occupied. As the fourteenth century drew to a close, the town’s walls were moved outwards to include this north-western area.

CITY WALLS

To see the last remains of the town’s outermost city-walls walls, leave the Hafner Platz by going West. Follow the Fischergasse as far as Schwedengasse and then turn right into the Schwedengasse. Immediately on your left there is a small fragment of city wall. Continuing on along this lane, brings you to a much larger, restored fragment. From here the Steiner Tor can be seen immediately ahead.

STEINER TOR

The Steiner Tor is named after the town of Stein, in whose direction the Tor, or gateway points. Going through the gateway and gaining a distance from it affords a better view. The two round towers date from the end of the fourteenth century. The central square structure was built a century later by Emperor Friedrich III. In 1477, Krems was besieged by the forces of the Hungarian King, Matthias Corvinus. Although the town was able to hold out, the encounter showed that old walls only offered partial protection against modern weaponary. Accordingly, the town’s walls were strengthend and its towers were made to protrude out further. This was so that defenders would be better placed to shoot at intruders attempting to scale the walls. In 1485, Matthias Corvinus sent a second force and the recently modernised defences successfully withstood the siege. On the outside of the gateway, next to the date 1480, there are the letters A, E, I, O, U. This is an abbreviation for „Earth Is Under Austrian Omnipotence“. Friedrich’s rule was challenged, not only by Matthias Corvinus but also by his own brother Archduke Albrecht VI, who was also unsuccessful. Friedrich’s ambitious motto can be seen as prophetic, for a few hundred years later Austria was an empire.

OBERE LANDSTRASSE 2

Return back through the gateway and follow the Obere Landstrase East as far as Farbergasse. At Farbergasse turn left and then at the end of the street, right into the Schlüsselamtgasse. Here you will pass the Schlüsselamt or Key Office. This was where the old city-walls were before they were extended. At the Key Office there was a gateway where the keys to the town could be borrowed. In times of danger the monks would abandon the monastery and seek refuge within the town. Following the Schlüsselamtgasse eastwards brings you to Krems Parish Church. Due to its size this church is also known as The Cathedral of the Wachau.

THE OLD HOSPICE

At the end of the Schlüsselamtgasse, look up to the left for a view of the Piarist Church. Below, on the northern side of the square, a ramp leads up towards the church. Leaving the Cathedral of the Wachau for later, cross the square and go up the ramp. At the top of the ramp, there is the entrance to the original Bürgherspittal, or Old Burgesses’ Hospice. During the Middle Ages this was here that the sick, aged and infirm were cared and provided for. In conjunction with the parish church the hospice was managed by the wealthy and privileged citizens who ran the town.

PIARIST CHURCH TOWER

After the Old Burgesses’ Hospice, a flight of covered of steps leads up the Piarist Church. This covered way is a Baroque construction and either side there are the original paths. Reflecting this, the central path on the right features a Gothic archway. For a view over the town follow one of these four ways up towards the Church.

An essential feature of any Medieval community was an outlook tower. This was manned by a look-out who would raise the alarm whenever a band of brigands or the troops of marauding armies were sighted. It was from such a tower that the Wachau owes its name. The word is an abbreviation of die Wache in der Au or, the watch tower in the marshes. In Krems the outlook tower was the Piarist Church tower. Look out for the Romanesque windows which hint at the structure’s ancient origins. When times became more settled, such towers were still manned so that the alarm could be raised when fire broke out

THE PIARIST CHURCH AND THE REFORMATION

The rest of the Piarist Church is for the most part Late Gothic. This was a Renaissance style that derives from the Gothic of the Medieval Ages. During the Renaissance, Krems and the Wachau were largely Protestant. In Krems, the Piarist Church was popular with the burgesses of the town and those of Protestant persuasion. In the square down below, this resulted in the parish church becoming so neglected that it fell into a state of disrepair.

In 1568, Emperor Maximillian II had allowed a degree of religious freedom for Protestants in the Habsburg Empire. This was through his partial acceptance of what is known as The Augsburg Confession. Full acceptance was dependent on the drawing up and printing of an agenda. This was an order of church service that had to be followed. Prior to being printed the agenda required imperial approval. Initiated by Protestant nobles in the Wachau, the first draught of The Agenda was written in Spitz in 1569. For this difficult task, the Protestant theologian David Chyträus was summoned from Rostock. Chryträus’ text was however only accepted after it had been worked over by Christoph Reuter. Some years before, Reuter had bought a property near Stein. To avoid upsetting the Catholic fraternity at Court, Maximillian was never announced his approval. Instead permission to print was granted on the condition that the operation be carried out in secret. Hidden in the woods above Stein, Reuter’s recently acquired property appeared to be perfectly suited. Thus during the summer of 1470 a temporary printing workshop was set up at Scheibenhof. The first copies of The Agenda were printed in the autumn of the same year. Not as remote as assumed, whilst the Emperor was away, word leaked out that something subversive was going on. This resulted in the printer and his assistants being arrested. When the Emperor returned the matter was clarified and the prisoners released. Nevertheless printing was transferred to the more remote location of Rosenburg and only resumed the next year.

THE PIARIST CHURCH AND THE JESUITS

Following Maximillian’s death in 1576, the imperial throne was inherited by Rudolf II. Like Maximillian, Rudolf had Protestant sympathies. These sympathies were however not shared by his brothers and others at Court. Following the rise of Protestantism, the Catholic fraternity worked hard at promoting the Counter-Reformation in Bohemia, Hungry and Lower Austria. This eliminated Protestantism from the region and the Piarist Church was given to the Jesuit Order. This order was found explicitly to restore und rejuvenate Catholicism. In 1658, a series of sculptures with frescoed backgrounds was made. This leads around the outside of the Pirist Church and show the Passion and suffering of Christ. The story begins at eastern end of the church with The Agony in the Garden of Gethsemene. There then follows, The Flagellation, The Crown of Thorns and The Presentation of Jesus as King of the Jews. These scenes are followed by The Carrying of the Cross, The Crucifixion and Christ in the Tomb. Meanwhile, below the Pirist Church, the delapidated parish church was rebuilt in an opulently Baroque style.

After the Story of the Passion follow the Piaristengasse East. A major focus of the Jesuit Order was teaching and a school was founded. This is the Piaristen Gymnasium or Piarist Grammar School which is what lies behind the high walls.

HOHE MARKT

The Piaristengasse leads out into the top end of the Hohe Markt. Follow the slope down towards the lower end of the square to see the castle. During the twelfth century this was where the Kremser Pennies were minted. During the thirteenth century the entire complex transformed into a Medieval palace. This is the Gozzoburg, named after the tax-collector and financial administrator, Gozzo. To the left there is Gasthaus Jell where regional cooking may be enjoyed. Behind the Gasthaus there is a house which was once a chapel. This is the Katherina Chapel. First mentioned in 1503, the frescos inside the house can be seen by scanning the QR code on the information sign.

WEGSCHEIDT

After the Katherina Chapel, go East. Then turn South to follow the Wegscheidt down a steep slope. At the bottom of the slope, at Wegscheidt 1, lookout for a derrick. This once a common feature serves as a reminder that the prosperity of Krems was built on trade. In the attic spaces of houses, commodities were used stored prior to sale. Where the neighbouring town of Stein had the right to trade in salt, Krems concentrated on ironware. Unlike Krems, the twin town of Stein lay directly next to the River Danube and so could offering mooring facilities for barges. Yet Krems had the advantage of lying on the North-South land route that lead from Prague to Venice. As these advantages were balenced, the prosperity of the two towns was very much linked.

MANHOLE COVER

From the Wegscheidt veer left down to the Unter Landstrasse, or Lower Land Street. Follow this road as far as the ironmongers’ Neunteufel. Here, in the middle of the road there is a manhole with a double-headed eagle. This testifies to an important event in the interwoven histories of Krems and Stein. Although run seperately, many decisions were made jointly. This included an important decision made in November 1462. In 1457, a dispute had broken out between Emperor Friedrich III and his brother, Archduke Albrecht VI. This was prompted by the death of the king of Bohemian and Hungary, Ladislaus Posthumous. The young king’s sudden death lead to the brothers arguing about who should take over the vacant thrones. Renouncing their loyalty to the Emperor, the Viennese favoured Albert. At first Krems and Stein also sided with Albrecht but then the councillors changed their minds. When Friedrich was besieged in his castle in Vienna, the twinned towns sent ninety soldiers to support him. This tipped the balance and as a sign of gratitude the towns were granted privileges and favours that greatly enhanced prosperity. These included the right to insist that all goods passing through should be offered for sale before being allowed to proceed. Only if no local merchant was interested in buying, were goods cleared for an onward journey. As shown by the manhole cover, the Emperor also granted the two towns, the right to use the imperial eagle as a coat of arms.

SMALL SGRIFFITO HOUSE

From the ironmongers’ follow the Untere Landstrasse towards the river and the site of the town’s eastern gateway. With the increased wealth and prosperity that the sixteenth century brought, houses in Krems were modernised. Merchants would buy up two or three adjoining Medieval houses and convert them into single, spaciously laid out dwellings. The facades of these houses were then adorned, either with sgraffito or with sculptures and frescoes. At Untere Landstrasse 69 there is an example of such a house decorated with sgraffito. This is known as The Small Sgraffito House. Built in 1561, the dyed plasterwork shows scenes taken from fables, the Old Testament and from daily life.

GATTERMANN HOUSE

Retracing one’s steps back along the Untere Landstrasse, at Number 52 there is the Gattermann House. This is easily recognisable by an ornately decorated bay-window built on the corner, that extends over two stories. Both round and rectangular bay-windows were built so that proud house owners could look out over the street and show themselves to the world. Such citizens would send their children to universities as far afield as Padua in the South and Jena in the North. Trade contacts extended from the Mediterranean to the North and Baltic Seas. Those who could afford to, wore cloth from Flanders and seasoned their food with spices that were imported from the East via Venice.

In the Gattermann House the burgesses would meet. Over a glass of wine in a convivial and sophisticated atmosphere, they would discuss politics, topics of the day and themes of interest. This included the things they read in books and the new religious ideas coming from Germany. In 1559, 29 burgesses met in the Gattermann House, each drawing their coat of arms on the upper part of the wall. By no means confined to Krems, the burgesses owned a house in Vienna. Here they could stay for prolonged periods of time and by lobbying, could play a part in national politics and policy-making.

SIMANDL FOUNTAIN

Continue on back along the Untere Landstrasse. At house number 57, there are Late Gothic window frames that also date from the Renaissance and which are now rare.

Further on, at the bottom of the Wegscheidt, a stone statue adorns a fountain. This testifies to the existence of another gentleman’s club, The Simandl Club. This is first recorded in 1529. In Austria and Bavaria, Siman is a slipper-shod, armchair hero. According to oral traditions in Krems, he was a hen-pecked husband. As the sculpture shows, when he wanted to go out at night, he had to beg his wife for the key to their house.

LARGE SGRIFFITO HOUSE

From the Siman Fountain, follow the Untere Landstrasse along the high street to number nine. Then turn right and follow the winding steps up to the Althangasse. Here there is the Large Sgriffito House, with sgraffito decorations that are spread over two stories. As at the Small Sgraffito House, fables and scenes from The Bible are shown, along with motifs from daily life. Among the musicians depicted there is one playing a bagpipe. Other scenes situated higher up, show a merchant’s journey to Russia.

TÄGLICHER MARKT

From the Large Sgriffito House retrace your steps back to the Unter Landstrasse. Turning right, continue on along the Untere Landstrasse to the Täglicher Markt. Here the Obere and Untere Landstrasse meet. As the name implies, this Daily Market was the market-place for the new town. At the intersection, each of the four houses was adorned with a personification of one of the four seasons. Above the apothecary, there is a personification of Summer. Meanwhile the house diagonally opposite shows Winter warming his hands over a brazier. The sculptures were painted and Summer was shown with a dark tan. For this reason the apothecary on the ground floor is known as the Moor Apothecary. Today the original statue, complete with its paint can be seen in Museum Krems.

APOTHOCARY’S HOUSE

In 1532, the house and apothocary at Obere Landstrasse 1, was destroyed by fire. This is recorded by an inscription on the Obere Landstrasse side of the house, just below the statue. The inscription reads “In this year of 1532 when Emperor Charles waged war against the Turks, this house was burnt down. But within two years, Wolfgang Kappler, medicus, built the same”.

Around the corner, above the personification of summer, there is a relief that depicts a wild man. In one hand he holds a pruning knife, with the other he supports a coat of arms. The motif of the wild man derives from the Roman god, Silvanus. Silvanus was thought of as a friendly god of woods, who planted trees in desolate places and tended to saplings. He was also a god of herded animals. Wild men are a feature of Slavic and Germanic folklore. They also occur repeatedly in Medieval and Early Modern Age art. The wild man who supports the Kappler arms, wears a woven crown of foliage that spirals up into a point.

Wolfgang Kappler was born in Strasbourg. Coming from a wealthy family, hewas able to study medicine in Venice. Thereafter he practised as a physician in Brno, in the Czech Republic. From there he moved to Znaim, where he was an apothecary. In 1527, he was invitated to be a burgess of Krems. Accepting the invitation, Kappler bought the house on the Täglicher Markt and moved to Krems. Of Kappler’s wife, Magdalena Gmundner, little is known. The daughter of a baker she was the mother of the couple’s thirteen children. In Museum Krems there are portraits of the couple along with apothecary’s jars that date from the period.

WILD MEN AND SPECULATIVE THOUGHT

During the Renaissance, a collection of texts known as the Corpus Hermeticum was of great importance. This was thought to have been written by a thrice-great Hermes. In the inscription below the wild man, there is a reference to one whose greatness is also three-fold. This is Emperor Charles V, who was king of Spain, Austria-Hungary and the Spanish Netherlands. The inscription records that Kappler’s coat of arms was given to him by the three-fold king/emperor. The implication is that if there is a thrice-great king on Earth, there is also a three-fold king in the world beyond. This is suggested by elements in the arms that corrolate with motifs of the Corpus Hermeticum.

The Corpus Hermeticum taught that at the heart of each individual, there was a spark of divinity. If kindled, this spark had the capacity to radiate. Through ignorance and bad habits however, the spark was all too often stifled and suffocated. On the skin of a neglected and ill-kept body, it was but an animal hide of sensory impressions. Yet if purified, it could abandon the hairy hide and ascend up towards the true light. The inscription asserts that the corporal and mortal bearer of the arms should address and pay homage to that which is divine. This suggests that the pruning knife held by the wild man is an emblem of purification.

THE GÖGL HOUSE

At the Täglicher Markt, the top of the house on the south-western side is ornamented with coats of arms. Below, a juxtaposition of Medieval and Renaissance images show scenes from daily life. Coats of arms were originally emblems of the aristocracy and landed gentry. During the Renaissance however, they were bestowed with increasing frequency on burgesses. This emphasised their position and status within the community. Soth of this once colourful house, there is the Gögl House. This is graced by a Late Gothic bay-window which formed the eastern end of a chapel.

DACHSBERGGASSE

Continue West along the Obere Landstrasse. At number three, turn left into the Dachsberggasse. Towards the end of the street, there is an impressive courtyard with arcades that extend over two stories. Here the coats of arms of the people who once lived in the houses are rendered in sgraffito. Like bay-windows, arcades enabled residents to see and be seen. Yet they also allowed rooms to be accessed individually. Thus with the new architecture, there was also an increase in privacy.

THE NEW HOSPICE

Retrace your steps a little and at Dachsbergergasse 4, go through the archway. This brings you into a courtyard. Here there is an arcade with simple, rounded arches. This complex of buildings formed the new Burgesses’ Hospice. Completed in 1470, it was built on the site of the Jewish Ghetto. This the Jewish community in Krems had been forced to abandon fifty years before. During construction work, a pot of gold coins was found, doubtless buried by a worried Jewish citizen. The burgesses saw this as a gift from God and used the money for the building of a hospice church. Yet Friedrich III saw the find as his. Invoking treasure trove, he demanded that two thirds of the 450 Gulders raised from the sale of the gold be paid to him.

THE VAULTED ROOM

Continue on into the courtyard and turn right. This brings you into a vaulted arcade that leads back to the Obere Landstrasse. This was once a closed, interior space that was used for festivities and official purposes. On the western side, three doors lead from the Hospice complex into the room. On the eastern side a single door leads into the Hospice Church. It is likely that this is where the statue of Saint Vitus in a Vat, seen in Museum Krems, originally stood. Facing West, every day people going from the Hospice to the Church, will have seen the Saint deep in prayer. For the residents, this confrontation with the healing patron of the town will have offered solace and comfort.

THE NEW HOSPICE CHURCH

At the Obere Landstrasse, before continuing turn back towards the right. This brings you to a Gothic doorway which is the outside entrance to the Burgesses’ Hospice Church. Above the door, as at the Steiner Tor, there are the initials of the Emperor’s motto, A, E, I, O, U. These were carved as a message of thanks to the Emperor for his donation of 150 Gulders. Inside there is a gracile inter-laced fan-vaulted ceiling. This typical of the Late Gothic style and is characteristic of many churches in the Wachau.

The Burgesses‘ Hospice Church is dedicated to Saints Phillip and Jacob. A Renaissance detail that deserves attention is the tabernacle on the right-hand side of the main body of the church. Such tabernacles derive from a synod decision made in 1274 in the Diocese of Passau. This decreed that the consecrated but not yet dispensed sacraments, were to be kept in secluded space. There thus arose a tradition of making intricate wrought-iron grating’s. This tradition continued into the sixteenth century, with the example in the Burgesses’ Hospice Church being particularly fine. Use the zoom of a camera or phone to look more closely. At the top, Christ is shown as the Judge of the World. Below, there is a monstrance with Maria and Saint George on either side. In the next row there are three “I. H. S.” symbols. These letters stand for in hic salus, which means “in this sign”. Below, these invocations are followed by scenes from the Passion and hunting scenes. Above, a six-winged cherub announces the presence of God and bestows blessings.

TOWN HALL BAY-WINDOW

The building opposite the Burgesses’ Hospice is the back of the Rathaus or Town Hall. On the corner a sumptuously ornate bay-window hints that this is a municipal building of significance. At the Rat or advice house, citizens could and still do, seek advice. Below the soldiers and the coats of arms, the window is supported by a figure of Hercules fighting a lion. This stands for the strivings of the city and its burgesses to tackle the problems of the day.

TOWN HALL HALLWAY

At the window, turn right and follow the Kirchengasse up the gentle slope. This leads to the Pfarrplatz. On the South side of the Pfarrplatz there is a short flight of steps. This leads to the Krems Town Hall. Passing through the glass doors, one enters a large hallway with a vaulted ceiling. Here the capitals of the columns betray a lack of awareness. This concerns the difference between Romanesque capitals and the capitals of Antiquity. This ambiguity however prompted northern Renaissance architects and masons to invent new forms. In the Town Hall, there is a photocopy of a decree written on vellum. This is the decree stipulating that the Wachau was to be colonised by monasteries.

KREMS PARISH CHURCH

Next to the Town Hall there is the Cathedral of the Wachau already encountered. After years of neglect, the building was in an advanced state of dilapidation. In 1529 permission was granted for the building to be demolished. Yet there were delays and it was not until 1616 that a new building was begun. In 1589, the citizens of Krems and Stein had been urged to return to the Catholic faith. In front of the Town Hall in an act of open defiance, they had however had refused. For this, the trading privileges that they had enjoyed for over a hundred years were revoked. As a result many protestant merchants left and prosperity plummeted. Yet for the catholic fraternity at Court, the overriding aim had been achieved. Krems and Stein had been brought back to the fold of Catholic belief. The rebuilding of the parish church was thus a major Counter-Reformation statement. Outside the church does not look unduely ornamentated. Inside however, the full gamut of Baroque illusionism awaits. Designed by the Italian architect Cypriano Biasino, the fabric of the new building was completed in 1630. Enter and experience a vaulted space of Baroque opulence that is nevertheless harmoniously orchestrated. After completion items of church furniture such as the altar and were added piece by piece. One of the last contributions was the images on the walls and ceiling. These were painted in 1787, by Martin Johann Schmidt from Stein.

FOUR SEASONS HOUSE

From the Parish Church, go back to the Obere Landstrasse. Turning right, continue on West in the direction of the Steiner Tor. Along the way there are ornately ornamented Baroque facades. At the Steiner Tor turn right and walk up towards the Körnermarkt. At Schmidgasse 3 you will pass the Baroque house where Cypriano Biasino lived. At the end of the short street, at Körnermarkt 4, there is The House of the Four Seasons. This shows the four seasons in a Rococo style. This is a lighter style of architecture that followed the Baroque. On the corner there is a statue of a saint from Prague who is often depicted in Central Europe. This is Saint Nepomuk who was a patron of bridges and the confidentiality of confession.

KÖRNERMARKT

As the name says, at Körner Markt or Corn Market was where corn was sold. Yet starting from 28th October, for two weeks, the Corn Market was the Simon and Judas Market. Here saffron was sold. In the Wachau, from the Middle Ages up until the end of the eighteenth century, saffron was grown in large quantities . In 1786, a staggering 4.5 metric Tonnes of saffron was sold in Krems. At the centre of the square, there is a column topped by a Baroque sculpture of the Virgin Mary. On one of the bases below, a cherub with a sword drives a fallen angle back down to Hell. On another base, a cherub holds a fish while a third holds a cornucopia. These latter attributes are symbols of health and plenty.

THE DISSOLUTION OF THE DOMINICAN MONASTERY

The Counter Reformation and the foundation of the Jesuit Order meant that the Dominican Order was no loner important in combating unorthadox belief. This resulted in the Dominicans becoming an order that was dedicated to poverty. Unlike other orders they did not make anything or teach children. Accordingly, in 1786 Emperor Joseph II closed the order and the church became a button factory. Later the nave was used as storehouse and then as a fire brigade station. Meanwhile the apse was used as a theatre and later as a cinema.

Above the fire station, was where the recently founded Museum Krems was housed. At the end of the 1960’ies the first floor and partition walls that divided the space of the church were removed. In the nave the decorations date from 1260. In the apse they date from around 1320. Today Museum Krems is housed in the monastery buildings behind the church. Apart from telling the story of the town and the region, the museum also tells the story of wine and wine-growing. Information is available in English and German and the museum is an ideal place to continue learning about the region.

END OF THE KREMS TOUR

The tour of Krems starts with a model of the town that can be seen free of charge in Room 2 of Museum Krems. Thereafter a figure of eight route is followed through the old town where historic highlights are pointed out and explained. Included in this tour are developments in religous thought over the centuries: Medieval heresy, the Reformation and Counter-Reformation and the dissolution of certain monastic orders. If all items are listened to, a minimum of one and a half hours must be allowed. To open up the itinerary and start the tour click on the title above. Text: Alexander H. Curtis, all rights reserved.

Stein Tour: Salt, Houses, a Bridge and a River

Welcome to this Reloading Humanism tour of Stein. The tour works through the use of buttons which when pressed initiate a Google Chrome plug-in. This reads the English texts. Once started pressing the button again stops the reading. Pressing the button a third time restarts the reading from the beginning. Street directions are at the beginning of each tour item so that the repetition of instructions is straightforward.

WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE

At the Shipping and World Heritage Centre an open air exhibition gives an informative introduction to the history and culture of the Wachau. Look South across the river to sees the Benedictine monastery of Göttweig. Göttweig is old German for “Where God whiles”.

A HARBOUR

From the World Heritage Centre walk inland. Using the two zebra crossings leave both roundabouts on your right and cross the Steiner Donaulände. During the Middle Ages on the other side of the second round about there was a harbour. The harbour was discovered when the silver twisted cuboid building was built. This latter is The State Gallery of Lower Austria. At the harbour and all along the banks at Stein barges could moor close to the bank. They could thus load and unload their cargoes this being something that could not be done at Krems. Nevertheless Krems lay on the North-South route that lead from Prague to Venice. Accordingly the prosperity of the two towns was linked. For this reason, although run sepeartely many decisions were made jointly.

KREMSER TOR

Continuing on up the slope and taking the first left leads to the Kremser Tor or „Krems Gateway“. This is the eastern gateway to Stein and is so named as it faces in the direction of Krems. Built in 1470, the steeply pointed roof is a Renaissance feature. Stein occupies a narrow strip of land between the steep slopes of the plateaux above and the course carved out by the River Danube. Look up to the right to see the vineyards that overlook the town.

STEINER LANDSTRASSE 14

Passing through the gateway, on the right-hand side one immediately comes to Steiner Landstrasse 14. Although the fabric of the houses on the Steiner Landstrasse date from the Middle Ages, buildings were repeatedly adapted and rebuilt over the centuries so that today, the town is largely defined by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Earlier architectural fragments however abound such as here, where at Number 14 an extended bay dates from the Renaissance. This form of Late Gothic pipework was used as an adornment on doorways, window-frames and supports. Once common it is now rare.

GÖTTWEIGERHOF CHAPEL

After the Late Gothic pipework take the first right anf go through the archway. This leads to a second archway over which a Gothic chapel has been built. This is the Göttweigerhof Chapel which has an eight-sided tower. The chapel dates from the fourteenth century and so from the Middle Ages proper. As can be seen from the sign on the right hand side, the frescos that decorate the chapel, hallway and oratorium are important examples of Gothic fresco painting. The interior also features rib-vaulting and niches.

For those who can spare the time, the key to the chapel can be borrowed from Museum Krems. During the winter months (when the museum is closed) the key is available from the city’s Cultural Office which is situated above the museum on the second floor. Borrowing the key costs € 2 per person and includes a highly informative folder which is available in either English or German.

THE GÖTTWEIGERHOF

Going through the second archway brings one to the Göttweigerhof or “Göttweig Courtyard” itself. So that they would be self-financing monasteries were granted extensive areas of land. Over the centuries was then added to through wills. Like many monasteries the monastery at Göttweig owned land on both sides of the River Danube. Land was let out to tenants on a tithe basis with the monastery specifying which crops were to be grown. Once harvested the tithes were delivered to central depots where everything coming in was counted. The Göttweig Courtyard was the agricultural collecting yard for Göttweig Abbey. It was also where the farm factor lived who oversaw operations. Here, crops such as wheat and barley were stored while grapes were pressed to make wine.

Crossing the courtyard and going through a third archway leads out of the old town. Turning right and looking at the eastern wall, one can see that the outer buildings have a defensive character. As can be seen on the landward sides of the town, beyond the walls, there was once a protective ditch. Return back through the Göttweig Courtyard. At the Steiner Landstrasse turn right and carry on along the high street towards the West.

SALT STEADINGS

At Steiner Landstrasse 27 and 27a, two imposing houses form the southern side of the Minoriten Platz. In these Salzstadl or “Salt Steadings”, salt was stored prior to re-sale. Built in 1579, they testify to the importance of salt for the town. Rock salt was mined near Salzburg in an area known as the Salzkammergut and was then shipped by river to Stein. This was done using craft that increased in size as the salt was carried first along the tributaries of the River Traun and then along the Traun itself, down towards the Danube. As Krems had no access to the river for hundeds of years only Stein had the right to buy and sell salt. Although this privilge was hotly disputed, Krems was only ever able to acquire the privilage intermittently.

In 1457, following the death of the King of Bohemia and Hungry, Lasislaus Posthumus, a dispute broke out between Emperor Friedrich III and his brother, Archduke Albrecht VI. Here thedispute was about who should take over the vacant thrones. During the dispute salt was a major item of contention with Albrecht claiming the salt mines in Hallstatt and Friedrich those at Altaussee. As the dispute disrupted trade, the two villages resolved the problem by signing a treaty. For Krems and Stein however this was not an option as they were too close to Vienna. Renouncing their loyalty to the Emperor, theViennese favoured Albrecht. At first Krems and Stein followed suit. Later however the councillors decided to remain loyal to Friedrich. Thus when in 1462 the Emperor was being besieged in his castle in Vienna, the two towns ninety soldiers to support the Emperor. This tipped the balance and as a sign of gratitude, Krems and Stein were granted privileges and favours that greatly enhanced prosperity. These included the right to insist that all goods passing through the two towns be offered for sale. Goods could only proceed if no local merchant was interested in buying them. The dispute came to an end when Albrecht died soon after without an heir. Inside the Salt Steadings there are closely spaced, thick beams. These were specially designed to support the weight of the salt stored on the first floor. Salt was stored on thefirst floor as only then was it was safe from floods. On average floods happened every five years and were often a result of snow melting in the spring.

THE REBENTOR

Continuing on along the Steiner Landstrasse, pass through Ludwig-von-Köchel-Platz and approach the Church of Saint Nicholas. Before looking at this lower church, those who can should climb the steep steps that lead to the upper church. This is Lady Hill Church and it was on this rocky outcrop that the beginnings of Stein as a settled community are to be found. The first people to live here were Slavs who inhabited the Northern banks of the Danube during the Late Roman Era and the Age of Migration. The current church stands on the site of an older church that dates from the eleventh century. The foundations of this older church stand in turn on a structure that dates from the Roman era. Pass through the base of the tower and continue on to arrive at the Rebentor, or Vine Gate. Either side of the Rebentor, the town’s northern wall once extended along the length of the Kellergasse.

THE WELL

Retrace your steps back to Lady Hill Church. Alternatively instead of going straight on, you turn right and follow the narrow flight of steps down. This leads to a well from which for hundreds of years, water was drawn. Once a busy meeting point, this is now a tranquil spot where a refreshing drink of spring water may be enjoyed. From here, turn left to return to Lady Hill Church.

THE CHURCH OF OUR LADY

During the thirteenth century, even though it was not yet finished the lower church was made the official parish church of Stein. Meanwhile the upper church was dedicated to the Virgin Mary. It thus became Lady Hill Church, or the Frauenberg Kirche as it is known in German. The church’s current form derives from the 1380’ies with the interior dating from around 1470. The fabric of the tower dates from late sixteenth century and is capped by a distinctive Baroque roof. The tower has seven stories and unusually there is a chimney. This is because up until 1970, the top floor was where a watchman lived who would keep a lookout for outbreaks of fire. In 1966, the church was dedicated to the memories of those who had fallen during the First and Second World Wars.

SAINT NICHOLAS‘ CHURCH INSIDE

Go back down the steps and turn right to approach the entrance of the new church. This is the Church of Saint Nicholas which as a building is first mentioned in the fourteenth century. The current structure however dates from the fifteenth century. Built in a Late Gothic style, inside there is a kind of webbed rib-vaulting that is typical for the region.

During the eighteenth century, the church was fitted out with a dominating array of Baroque furniture. These fittings enclosed large paintings by the acclaimed artist, Martin Johann Schmit who lived in Stein. At the beginning of the twentieth century, this black and gold furniture was replaced by much lighter Neo-Gothic fittings. As a tribute Martin Johann Schmidt a large altarpiece with a painting by the artist was allowed to remain. This is located in an alcove on the North wall and shows Saint Nepomuk. A side altar on the South side of the church also features a painting by Martin Johann Schmidt. This shows the church’s patron Saint Nicholas. Reflecting the importance of the river, both altarpieces address saints who may be called upon by those in danger of drowning. Both saints are shown in the process of saving people from watery graves.