In the wake of Plato and the tradition of the Nineteenth Century system builders, philosophy is often thought of as a subject in which the world is explained in cryptic terms that lie somewhere between the scientific, the religious and the esoteric. Philosophers are thus seen as people who, via arcane sentences printed in bulgingly thick books are able to access higher realms of knowledge and being that make them oblivious to the concerns of human care and worry.

The philosophical tradition that lies behind this caricaturised sketch is however as far removed from what Alain de Botton is about as one can get. Rather de Botton is concerned with ascertaining, in the here and now of today, „on the level“ principles by which we may live happier and better lives. What he has to say addresses the world we live and work in and which each day we have no choice but to face anew even when it seems that everything is against us. It is thus appropriate that in Krems a close known as „The Philosophers‘ Ladder“, is in fact a cul-de-sac that is about as level as one can get.

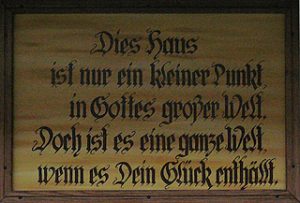

Several houses in the close feature artistically decorated façades with one house offering passers-by a verse of home-spun philosophy that points towards de Botton’s down to earth but nevertheless important mission:

This house is just a small point in God’s great wide world and yet it is the whole wide world if therein your joy be found.

De Botton’s writing has been described as constituting a “philosophy of everyday life” and he can be seen as continuing in the tradition of Epicurus for whom philosophy was useless if it did not help alleviate people of unhappiness and worry. Written for the general reader, de Botton’s books are unpretentious and fast moving. Their goal is to help people negotiate the confusing moiré of stress, frustration, rejection and failure that all so often characterise either our work lives, our private lives and sometimes both. Continuing on from his written work, de Botton has founded The School of Life. This is both a boxed set of books that cover all the major facets and events of life, as well as an international organisation that offers lectures, courses, seminars and therapy along with a series of regularly updated online videos.

There are also products such as packs of cards with questions, an emotional barometer and exercise books. While some of these products are designed so as to help us know ourselves better, others serve as teambuilding exercises. Like de Botton’s books, The School of Life is designed as a pragmatic corrective to the over romanticised and over hyped expectations that modern life and advertising instil in us and which, if taken at face value, invariably lead to disappointment. Passionate about architecture, de Botton has also initiated Living Architecture, a scheme in which top-notch architects design houses in the United Kingdom, which can then be rented out for holidays. The idea behind this is to enable people to spend prolonged and relaxing periods of time in spaces of real architectural quality. For many people the only chance to encounter and experience outstanding modern buildings is in places like airports, where we have other things on our minds than spending a relaxing time in a well-designed space.

In How Proust can Change your Life, de Botton extracts from Proust and his writings a number of philosophical principles and rules for living, one being that knowledge acquired through failure and suffering is more genuine than that superficially gleaned from pleasant experiences. Another relates to how we see and perceive things. The way we see the world is invariably laden with expectations and social codes that dictate what is of value and what not. This can lead to a way of life in which everything is about thinking about what the neighbours might think and little else. In other cases, such as that of the narrator of Proust’s masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, the problem is not of encumbering social codes but of ways of seeing things drawn from the past. While these do have genuine validity, they are Proust suggests, not necessarily capable of providing orientation in the here and now of the world in which we live. In this and other ways, de Botton derives from Proust, a number of guidelines for living, this leading to the book’s becoming a major international success. Yet the book is important as it shows that works of literature and thus by extension, all art can be examined from the viewpoint: “What does this work have to say about life and how it is to be lived?”

Although many of de Botton’s books are designed to help readers as individuals find resolution and solace to their own personal dilemmas, in Religion for Atheists, de Botton takes on the general case of society as a whole and rises to the challenge masterfully. In a penetrating analysis he shows how secular society, in abandoning religion, has become stilted so that anything to do with our inner lives is seen as belonging to a private zone which lies far beyond the remit of operation in which official institutions see themselves as being licensed to operate. In learning to follow the scientific method and abstract away from superstition, hearsay and blind supposition, we have turned our backs on and disowned our emotional selves. Trying so hard to make their subject objective, scientific disciplines, humanities departments have forgotten that the humanities are not dedicated to the investigation of an external reality that is independent of us but rather are focused on the world of the human which is massively influenced by subjective, inner realities. In a sense, in attempting to objectify the humanities, the baby has been thrown out with the bath water. Thus at universities, Proust and other authors are analysed in all manner of ways except that of reading the work with an eye to extracting observations on how our lives might be better lived. In the case of museums, labelling, layout and presentation invite one to believe that all that matters are the material circumstances under which a work was produced. Thus religious works of art hang in secularised spaces, out of place and out of time, with their original contexts of use and appreciation being by-passed and glossed over. Tacitly the subtext is: “People may have approached this work differently in the past but we, being superior, have no need for that sort of thing anymore”. For de Botton:

“No existing mainstream secular institution has a declared interest in teaching us the art of living.”

In this way, in secular societies of the modern age, there is the paradoxical situation that when it comes to questions of life and how it is to be lived, only religion is capable of offering any answers. And it is here that de Botton, an affirmed atheist, finds that if one is prepared to take the theology with a pinch of salt, the established religions of the world have a lot to offer. Thus he says:

“We should not let atheism get in the way of appreciating traditions that area part of a non-denominational heritage that was historically stamped out by secularists from a misunderstanding of the real identities of those who created it.”

As with de Botton’s book on Proust, Religion for Atheists, became a number one best seller, with even the Church Times finding it “surprisingly illuminating”. Always respectful of the fact that Christianity, Judaism and Buddhism evolved over thousands of years, de Botton shows how these religions have successfully accumulated a wide range of profound insights into the realities of human nature and the human condition. Moreover, he then goes on to show that if one ignores the theology, what they have to offer is of the utmost use and importance for us today and can help us conduct our lives as responsible adults, leading fuller and happier lives. The book is timely and has the potential to be hugely important. Run along the lines that de Botton sketches out, society would have the potential to be very, very different, with the chance of many more people living happier and less frustrated lives. In the case of museums, de Botton says:

“The challenge is to rewrite the agendas for our museums so that art can begin to serve the needs of psychology as effectively as, for centuries, it has served those of theology. Curators should dare to reinvent their spaces so that they can be more than dead libraries for the creations of the past. These curators should co-opt works of art to the direct task of helping us to live: to achieve self-knowledge, to remember forgiveness and love and to stay sensitive to the pains suffered by our ever troubled species and its urgently imperilled planet. Museums must be more than places for the displaying of beautiful objects. They should be places that use beautiful objects in order to try to make us good and wise. Only then will museums be able to claim that they have properly fulfilled the noble but still elusive ambition of becoming our new churches.”

Concerning universities, he says:

“The redefined universities of the future would draw upon the same rich catalogue of culture treated by their traditional counterparts, likewise prompting the study of novels, histories, plays and paintings, but they would teach this material with a view to illuminating student’s lives rather than merely prodding at academic goals.”

Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary would thus feature in courses on understanding the tensions in marriage instead of merely elements in a course with a title such as “Narrative trends in nineteenth century fiction”. Equally, the wisdom of Epicurus and Seneca would appear in courses about dying rather than in survies of Hellenistic philosophy. For de Botton, the aims of John Stuart Mill are to be returned to and embraced as a mantra for the new form of emotional intelligence orientated form of education that he envisages:

“The object of universities is not to make skilful lawyers, physicians or engineers. It is to make capable and cultivated human beings.”

De Botton advocates reinstating the Medieval notion of the soul as a sort of baby made of soul-stuff that at birth is inserted into a corporal body and which throughout life, needs care and attention. Following death, the soul was thought of as being released and if not immediately summoned to Heaven or sent down to Hell, was weighed by Saint Michael in a pair of scales with the Devil frequently trying to cheat by tipping the balance in his favour.

Abandoning the theology and leaving the metaphysics to metaphysicians, de Botton recommends that we hang on to the notion of the soul as

“a precious, childlike, vulnerable core which we should nourish and nurture on its turbulent journey through life.

The simple fact that each individual appears to have a soul-like inner dimension and that without this facet we are not human, means that as a moral philosopher de Botton is under no compulsion to define the notion any further. Nevertheless the metaphysical shortcomings of a world-view that cannot satisfactory explain our feelings of self are gaping and omnipresent. Twentieth century philosophy has repeatedly tried to explain the self away as nothing more than a chimera, with different schools adopting different strategies and ways of saying why that which is so fundamental to each and every one of us has no real standing at all. For Alexander Curtis the questions of „Who are we?“ and „What are we?“ are questions that must be answered if the level closes in which we live out our daily are to be given any form of foundation.

While one feels admiration at the way that de Botton dares to imagine a society run on wisdom and an acknowledgement of the frailty of human existence, one is also stupefied and horrified at the smug and narrow-minded bigotry that is still such a strong characteristic of atheism today and which has become institutionalised in nearly all official institutions. Philosophically, the ways of thinking that led to this institutionalising are inadequate and yet the mind-set still prevails and more-over, is an active detriment to both furthering the inner life of individuals as well as the collective well-being of society as a whole. Drawing from the lessons of Curtis’ Order at the Heart of Chaos, one might suggest that instead of distinguishing between the sciences and the humanities, one should distinguish between, physical sciences, “life sciences”, “cultural sciences”, history and prehistory and the humanities. Here, where the physical sciences are physics and chemistry, life sciences are all that has to do with the material realities of biological processes and life forms. Cultural sciences are then all aspects of behaviour exhibited by animals that result in and regulate group behaviour. This would include such phenomena as the honey dance of bees, the way that termite colonies are structured and maintained and the way that within groups of chimpanzees, allegiances are built up between individuals through grooming. It would also include the proto-linguistic behaviour and tool-making practices of all hominoids prior to the so-called Big Bang of human culture some 40,000 years ago (this being when modern human behaviour first made its sudden and striking appearance). Prehistory and history are then the chronological and sociological developments that relate to the culture of modern humans following the Big Bang, starting with the Aurignacian of the Upper Palaeolithic. This leaves the humanities as the study of human cultural artefacts at a level that goes beyond mere chronology and social function and which accepts that modern human artefacts were endowed with meaning that as far as it can be reconstructed must be entered into if the culture concerned is to be understood in human terms. This means nothing other than acknowledging the existence, in some shape or form, of some sort of soul as argued by de Botton and that it is (and always was this) that human artefacts are designed to address in addition to any purely material function that they may have.

A Baroque cherub in the cellars of Museum Krems serves as a reminder that the inner world of the self is akin to a child in need of care and attention

Fully aware of the distressing catalogue of perils facing the planet that is our only home, de Botton is aware that only happy people, for whom life is worth living, will have the motivation necessary to run our Earth in a sustainable manner. Thus we should take care not to forget ourselves and never forget that the inner child of the self needs care and attention as well. Here however, the lack of a metaphysical „place“ in which to conceive and locate the self continues to gnaw away in the background of our thoughts, undermining our ability to embrace the holistic world-view that we must embrace if we are to have a future. Returning to the „The Philosophers‘ Ladder“ in Krems, behind the houses, the trees and undergrowth hide abandoned wine terraces, that rise steeply and investigation reveals a steep and narrow path which tortuously zigzags its way up the hill and it can be assumed that this is the path from which the close derives its name.

The overgrown path and the remains of a cable lift that once straddled the slope bring to mind the crumbling edifices of „Continental Philosophy“, the kind of philosophy satirised at the beginning of this article and which strives towards the dizzy heights of abstract speculation.

During the nineteenth century, Continental Philosophy was taught in Krems at the Piarist School for a number of decades. Now however, it is difficult to imagine anything more out of fashion and open to being lampooned than the wish to construct a system of thought that explains everything.

Indeed the remains of the cable lift and a rusty iron basin raise the question of whether a metaphysical explanation of the self and its workings is possible at all and whether we will ever be able to escape the cul-de-sac of daily life and see ourselves as integrated into a wider, more encompassing whole.

Nevertheless, in spite of all, it is this task that Alexander Curtis takes on in his Order at the Heart of Chaos: Life and Consciousness in an Exploding Universe – that (within a ruthlessly pragmatic epistemology) the admirable work done by Alain de Botton might rest on more secure foundations.