All too often, the extent to which we are woven into and connected with the natural world is overlooked and underplayed. Further, when we do take time to consider our relationship with our environment, we automatically do so in a way that assumes that our relation to the natural world is a one way process of humans modifying their environment to suit their needs. The danger of this simplistic view is that it invites one to think that there is an original state to which any given landscape can be restored if man’s interventions are successively undone. This is naive and erroneous. Although we have influenced nature, nature has also influenced us and we are products of nature, including our capacity to mould, shape and change nature and we have been moulding the natural world for some 12.000 years. It was nature that, after allowing us to evolve, gave us the chance of becoming Neolithic farmers, dependant on cereal crops for the main part of our diet. Over millennia, the needs and demands of plants that we have cultivated have played a huge and often overlooked role in shaping and moulding human culture.

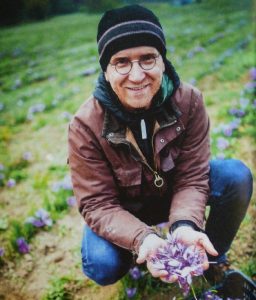

In the case of the ecologist and saffron farmer, Bernhard Kaar, it was an interest in the symbiosis between human beings and plants that lead him to saffron. Cultivated saffron is a crocus that, through mutation, lost its ability to reproduce sexually. In the normal course of events, such a crocus would have reproduced by continually dividing and splitting. In this way it would have expanded until the area to which it was adapted was filled with crocuses. As the nutrients needed by the plant became successively exhausted, the crocuses would have begun to die, so that after its proverbial “day in the sun”, all such mutations would have become extinct. Yet in the case of the cultivated saffron crocus, before this happened, a human being stumbled upon the colony and noticed that their stamens were significantly longer than those of the wild saffron crocus that had not lost its ability to reproduce sexually. This means that in human culture, the wild saffron crocus must have had a use and significance, for the person finding the mutant colony took some of the plants and transplanted them to a new location. In this way, some 5,000 years ago, the sexually impotent saffron crocus was saved from extinction. Genetic analysis shows that this took place in the area around Athens with all saffron crocus being descended from a single mutation. The Greek origins of saffron are confirmed by archaeology, with depictions of saffron and saffron harvesting showing that the plant played a role in Minoan culture.

The human interest in saffron is likely to have had a religious background, involving the symbolism of red and yellow and possibly also beliefs that saw the stamens as endowed with properties that we would describe as medical. Historically saffron has been ascribed with the ability to cure a range of ailments and was often used as an aphrodisiac. When investigated scientifically all such claims become difficult to substantiate so that one is left wondering whether the effects of saffron are not felt more in the mind than in the body. This shows that a plant can influence human behaviour simply by virtue of exciting the imagination without actually fulfilling any practical purpose. Soon enough though, saffron was used in cooking and from the early Middle Ages onwards was imported into Europe. With the crusades, saffron crocuses were smuggled back, leading in Austria, to a legend of a noble lady, Hulda von Rauhenstein, who promised her hand in marriage to whoever brought her the East’s most precious gift. Returning from the Crusades with a bag of saffron bulbs, an enterprising knight wooed her and was able to win her hand.

In this way, romance brought saffron to the winding and enchantingly beautiful valley of the Wachau in Austria. There, on terraces amid the vines of the vineyards, saffron was grown in significant quantities.

Hearing the story, Bernhard Kaar began to search the archives of monasteries in the area, to see if he could find any confirmation. After months of trawling through library catalogues, at the appropriately impressive Baroque library in Melk, he found what he had been looking for. Holding a slim A6 sized volume dating from 1797 in his hands, he realised that his life was about to change. Entitled Practical Instruction in the Growing of Lower Austrian Saffron, the book had been written by a monk named Ulrich Petrak, who described in meticulous detail how, in the Wachau Valley, the cultivated saffron crocus was to be grown and cared for.

The book had been written at a time when it was clear that for economic reasons, saffron wouldn’t be grown for much longer in the Wachau and not wanting this knowledge to be lost, the regional authorities had taken steps to ensure that a compendium be drawn up, recording all that was known about the plant. A retired abbot, Petrak at first conducted interviews, tapping into the knowledge of people who had grown saffron. Then he put everything he had heard to the test, growing saffron himself according to what he had been told. In this way he was able to understand exactly what was meant and was able to iron out misunderstandings and clarify inconsistencies in what he had heard. Realising that it was now for him to bring saffron back to the Wachau, Kaar bought the Old Railway Station in Dürnstein and following Ulrich Petrak’s instructions, he and his wife planted their first bulbs.

From these modest beginnings, step by step, they gradually expanded their sphere of operations. Founding a business, they now not only sell high quality saffron but also offer a range of saffron products and run a café where saffron products can be enjoyed whilst drinking coffee and admiring the view of the ruins of Dürnstein Castle.

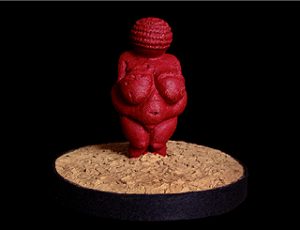

Also returning from the Crusades was Richard the Lionheart who though travelling in disguise, was nevertheless identified and was imprisoned in Dürnstein for having slighted the honour of Archduke Leopold V of Austria whilst they were in the Holy Land. Further upstream is Willendorf, the place where, 110 years ago prior to the building of the Krems-Grein railway, the Venus of Willendorf was found. Showing the symbolic importance of the colour red, this world famous prehistoric statuette was originally covered in red ochre, reminiscent of blood. The relevance of this to saffron is that in sufficient concentrations saffron will die water blood red.

At the Wachauer Saffron Manufactory, saffron is grown organically according to Demeter standards of production, these being higher and stricter than organic standards. Where conventional modern farming takes more from the soil than it gives, organic farming maintains an equal balance, each year giving back what it takes. Farming according to the Demeter standards however, leaves the land more fertile than it was before. Effectively it gives back more than it takes. In the case of saffron, the results are longer than average stamens of the highest quality. All the Kaars’ products are sold by direct marketing and although for customers the circumstances of production are not an issue, for Kaar, farming according to Demeter standards is an imperative that is not negotiable. Our evolutionary niche has evolved so as to make us wardens of the Earth’s resources and ecosystems and it is our duty to accept that we have been landed with these challenges whether we like it or not. Accordingly, we should therefore behave in a grown-up fashion and do the job entrusted to us with due diligence and to the best of our ability. This is not only ethical and ecological, in the long term, it is essential for our survival as a species. Following the same ethos, for the Kaar family it is of great importance that their employees are happy in their work and have a connection to what is being done. The same care and attention is given to the developing of products and so is handed on to the customer. Products from the Wachauer Saffron Manufactory are developed over extended periods of time with nothing being rushed into or hurried. So far, the product that took the longest to develop was a saffron chocolate, which took a full five years before the recipe was “just right”.

For Kaar, working with saffron teaches patience and calm. “Nothing can be forced through, everything has its hour”. This is easily seen when one considers that five people working for eight hours, first at harvesting and then picking out the red stamens, produce on average a mere twenty grams of dried saffron.

Although the Kaar family cannot ignore commercial and other considerations, the concerns of the business are never just about maximising profit. Rather the focus is centred on an equation, where as many terms as possible should balance out and in residual products there should be as little wastage as possible – both in terms of resources as well as in terms of human effort and motivation. The Wachauer Saffron Manufactory is thus about innovation and about how, by bringing saffron back to the Wachau, the valley can re-connect with its history and people can be given the opportunity of doing work that has meaning for both them and the region. To this effect, workshops are conducted with schools so that future farmers will know that growing saffron is always an option should they wish, or need to diversify. At the other end of the spectrum, the company also respects the people who buy its products and at seminars people can learn about saffron and experience first-hand, through comparing samples, how saffron flavours and modulates the taste of what we eat. One can learn how to distinguish real saffron from fake saffron and why it is that saffron from the supermarket does not and cannot match the quality of that produced by an artisan producer. Here however, the monopoly does not remain with the Kaars and in August, bulbs can be bought that two months later will flower. The cloned descendants of those bulbs that first mutated in Crete, the bulbs will split and divide, so that rapidly a kitchen garden supply can be cultivated, supplying the average household with all the saffron it needs. As the Kaar family shows, there are ways of doing business that treat the environment, employees and customers with respect and which enable interactions to take place that enrich the world around us, rather than cynically milking whatever there is to be milked and asset-stripping the world of its resources.

Here it must be admitted that businesses such as the Kaars’, only function due to their being enclosed within a macro-system that is as dependent as ever on perpetual growth and exploitation. Nevertheless this does not mean that it is contradictory or pointless to initiate such projects. In developing new ways of economically interacting with each other, there is no drawing board from which a new start can be planned. Rather, that which is already there must be slowly changed and adapted. As always, someone must lead the way and as one of many but still way too few, this is what the Wachauer Saffron Manufactory does.

The saffron grown in the Wachau was sold in Krems at the Simon and Judas Market that, starting from 28th October, was held for two weeks immediately after the saffron flowers had been picked and the stamens removed and dried. The selling of bulk quantities of saffron is described as taking place on a square in the town where a church was situated. With the Dominican Church forming its eastern side, this makes the „Cornmarket“ or Körnermarkt in Krems (previously known as the Korngries and Kreissamtsplatz) a likely candidate for the place where in 1776, a staggering 4.5 metric Tonnes of saffron are recorded as being sold.

Though neither grain nor saffron are sold here anymore, Bernhard Kaar’s saffron products can be purchased at the Museum Krems gift shop, which along with the museum itself, is housed in the buildings of the former Dominican monastery. The museum includes an exceedingly fine collection of sculptures, including the original Baroque statute of the Virgin Mary that stood atop the column that stands in the middle of the Körnermarkt and so will have overlooked the weekly selling of corn and the yearly sales of saffron.