Maja Göpel is a political economist, transformation expert and sustainability scientist. For her doctorate she investigated the history of economic theories with a view to establishing how such a cold and sterile notion as the Homo oeconomicus model of what a human being is could become so well established in mainstrean economic thinking. This she felt was a major factor that stands between us and the development of a sustainable form of life and society. Maja Göpel started working for the World Future Council in 2006 and from 2008-2012 was Director of Future Justice in the Brussels office. From 2013-2017 she was head of the Berlin office of the Wuppental Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy and then from 2017-2020 was General Secretary of the Scientific Advisory Group of the German Republic’s Global Environmental Change administration. She is an honorary professor at Leuphana University in Lüneburg and was a founding member of Scientists for Future. Along with many other posts and functions, she is a member of The Club of Rome and of the World Future Council.

In her book The Great Mindshift, How a New Economic Paradigm and Sustainability Transformations go Hand in Hand, published in 2016, she investigated the transformation of systems, political economics and the management of change. In her bestselling Thinking our World Anew – an Invitation (only available in German), she argues that the world’s problems are inter-related and three-fold with the nature of the problem being environmental, the growing divide between rich and poor and an erosion of democracy due to the misuse of social media. Although in identifying these themes, Maja Göpel echoes concerns already voiced by others, this is so as to, having understood the nature of the problems that need to be addressed, then use her knowledge of interdisciplinary strategies as a means of approaching and tentatively offering solutions to the crises that humanity faces. Like Lisa Herzog, Maja Göpel rejects the notion of Homo oeconomicus as a model of what a human being is and cites the so-called „Easterlin Paradox“ which, as she points out, is only a paradox for economists interested in propagting the myth of perpetual growth. Over a period of 25 years Easterlin corrolated the economic data from 19 countries with personal surveys conducted with individuals and found that, given continual economic growth, after a certain point, personal satisfaction stopped growing. This means nothing more than that once a certain level of comfort and security has been reached, additional wealth no longers brings additional happiness. After the destruction of cities and infrastructure brought about by World War Two, taking the GNP of a country was an easy and reliable method of establishing how contented the people of the country were likely to to be. Yet as Easterlin showed, after a certain point, additional wealth does not generate additional happiness. Paraphrasing the words of Robert Kennedy, „GNP measures everything except that which makes life worth living“. Nevetheless, as the model of continual growth had worked so well, no one in postwar mainstream economics thought of questioning it, whilst the rapid expansion of the European Economic Comunity opened up new markets and lead suport to the idea that continual economic growth was something that was, in the medium term at least, both sustainable and desirable. When these markets became saturated, Thacher and Reagan pushed the process of globalisation so that again, ever new markets might become accessible and the contradictory notion of perpetual economic growth in a world with finite resources became propagated as an economic creed. As perpetual economic growth and the notion of Homo oeconomics are the two sides of what is really a single coin, in her analyses of capatilism, Ulrike Herrmann, does not mention Homo oeconomicus and does not need to, as in debunking perpetual growth, the notion of an insatiable and ever consuming entity that both drives and thrives upon perpetual growth, is also debunked. Nevertheless, as Göpel observes, the myth of perpetul economic growth, the mis-lead notion that ever-increasing wealth leads to ever-increasing happiness and the myth of Homo oeconomicus, were used as justifications for the necessity of globalisation and the free-ing up of markets and after thirty years are still an essential part of orthadox economic thinking. Where Göpel and Lisa Herzog debunk Homo oeconomicus by citing empirical evidence that shows that this is not how people think and behave and Herrmann focuses on debunking the notion of perpetual growth, there is however a third way by which this sick and cynical notion of what a human being is may be called into question. This consists of developing a philosophical model of the self that makes us morally aware beings. Here, modern philosophy, despite its triumphs and many meanderings, has failed to come up with anything, nevertheless a mathematical model developed by Alexander Curtis achieves just this purpose and once some additional mathematical work, that relates the model to chaos theory, has been completed, a print-on demand booklet will be made available.

Arguing for a new form of global trade not dependent on continual economic growth, Göpel declares it the task of governments and states to treat nature as an asset that must to be actively secured and protected in order to ensure the common good. Of singular importance, she sees the problems that the world faces as being a collusion of cultural problems that are not simply technical or economic. Put simple terms, if we were to behave differently, things would be different. If we were to behave differently, technological solutions would have a chance of delivering what is required. As it is however, technology and the environment can never satisfy or sustain an ever-growing demand for more of everything. For Göpel, if the world’s problems are to be genuinely solved, the underlying impetus for change must come from the individual, with the first step being nothing more advanced than ensuring that the themes of the environment, democracy and defaunation are raised and that we continue to talk about them. In both Thinking our World Anew and the later, We can do Better. Setting out into Tomorrow’s World (2022, likewise only available in German), the aim is to bring the themes of transformation and change to a wider readership, pointing out that letting go of the idea that we must have ever more of everything, is not necessarily bad but rather would enable us to enjoy life more than we do now. To this effect, where in Thinking our World Anew Göpel advocated a coming out and a voicing of environmental concerns, in We can do Better, she indentifies the notion of a „Happ“, someone who in a way that is appropriate to them and their personality, acts as a catalysor and a prompter, opening up receptivity for the new and the sustainable. Here we all have a part to play and the Happ is anyone who aids and abets, both the happening of things and being happy and so by example and inspiration, plays a part in „making it happen“.

In We can do Better, from the specialist worlds of sustainability and transformation studies, Göpel takes examples and sketches out a much needed roadmap to a sustainable future. One of the opening motifs of the book is Peter and Paul Lake in Canada. On the map, this to be found in the wilderness below the “wolf’s head” of Lake Superior.

The two lakes are kettle lakes formed by huge lumps of the ice left behind by retreating glaciers. Although separated by a narrow causeway of stones, water seeps and flows between the two, making the lakes idea for studying fish populations, as it enables an experiment to be conducted in one lake, whilst the other serves as a control.

In 2008, there were 39 large mouthed bass and the population was stable due to minnows eating the bass hatchlings and so keeping the number of bass adults in check. To the 39 large mouthed bass an additional twelve were added to Peter Lake, followed by another thirty a year later. Apart from keeping the large mouthed bass in check, prior to this, the minnows and other non-predatory fish had also kept the water-flea population in check so that the algae on which the fleas fed, flourished, giving both lakes a green appearance. As the bass population in Peter Lake began to explode so the minnows were reduced and the dynamics of the situation resulted in their avoiding the middle of the lake and keeping to the shallows. This caused the water-flea population to explode, resulting in the elimination of the algae and the disappearance of the water fleas as soon as there was no more algae for them to eat. The result was that Peter Lake became crystal-clear whilst Paul Lake remained green. While all this was predictable, Carpenter’s aim was to try and ascertain whether, during the process, the approach of the point of no return in the eco-system could in some way be identified. Counting the fish caught in traps every day and then analysing the results afterwards and conferring with colleagues, it was found that prior to the point of no return, the non-predatory fish were scatted throughout the lake in irregularly occurring groups. These sporadic blotches of remaining population were the herald of a point of no return, which once traversed, meant that the population of non-predatory fish could no longer be saved even if all the bass were to be suddenly removed. This is because in any stable population there must be a reserve which allows for eventualities. Putting this in human terms is the book and film Into the Wild which tells the true story of Christopher McCandless, who after two years of adventures in North America lived alone in the wilderness of Alaska and survived for four months. This accords with the average survival time of nine months for a human being living alone in the wilderness. A group of five people meanwhile is reckoned to be capable of surviving for five years. If stability is to be attained however, a group of seventy people is needed and in such cases culture plays an essential role in bonding individuals together. Returning to Peter and Paul Lake, these considerations show how in breeding populations, stability and the point of no return at which instability begins, are both a long, long way away from the last breeding pair.

Not mentioned by Göpel in We can do Better is chaos theory which underlies what is going on such cases and enables a process to be understood mathematically so that in theory at least, it can be made predictable. Chaos theory has such a wide range of application that one of the constants, associated with it, delta, is known as “the universal constant”. In chaos theory, dynamic systems are investigated by plotting rate of growth against time. In the case of living things, the growth of a population is off-set by mortalities caused by old-age, predators and illnesses. Assuming all things to be equal, these can be lumped together or alternatively, one over-riding factor can be considered so that what one is looking at is a pair of competing factors, such as the bass and the minnows, the minnows and the water fleas, or the water fleas and the algae. Yet when one tries to consider all the components of an eco-system taken as a whole, all interacting with each other at once, the task becomes impossible. Due to the mutual interactions in such “fundamentally complex systems”, unpredictability and a degree of indeterminateness are inherent. Despite the name, fundamentally complex systems can however be surprisingly simple and begin with the gravitational interactions of three balls, or two balls with the Earth as the third solid body.

A double-jointed pendulum which, if imparted with a powerful flick of rotational energy, will flip chaotically round about and back and forth in a manner that is completely unpredictable.

The motion of the planets of the Solar System around the sun, whilst not being chaotic, is also not stable but rather is semi-stable. For more on chaos theory, see the second half of the essay European Pragmatism, accessible via the Reloading Humanism Mission Page. Chaos theory puts in context the significance of Carpenter’s experiment at Peter and Paul Lake, for despite the indeterminate nature of what was going on, signs were found that indicated that the system was about to undergo an irreversible change. Göpel and others point out that the erratic behaviour of the weather across the globe is thus possibly a sign that with respect to the world’s climate and weather patterns, we have may have reached a point disturbingly close to a point of no return. If this point is overstepped, then weather patterns, instead of being disrupted and erratic, will become chaotic, with it taking decades and possibly even centuries for stability to return. This dismal picture is further underlined by the concept of planetary limits in which climatologists identified nine systems with limits that should not be overstepped. The systems are the climate, the world’s oceans, its freshwater cycles, biodiversity, the areas of woodlands and forests, moors and grassy areas, along with the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles. Of these nine systems, five are now seen as having left the zone of safe operation and are accordingly in a phase equivalent to the sporadic groups of non-predatory fish in Peter Lake.

The message from Peter and Paul Lake is thus grave in the extreme, nevertheless Göpel warns against an over hasty war on symptoms and argues that diagnosing the underlying causes and taking informed corrective measures would get to the heart of the problem and be much more effective. Here she cites the case of Tanaland, a virtual experiment that was carried out in the 1970’ies. In this experiment, a group of hunter-gathers and a group of farmers live near a lake and whilst their lives are hard, their existence is stable and assured. A group of students was then invited to introduce measures that would improve the lives of the two groups. Woods were felled, machinery was introduced and insecticides and fertilisers were used on crops, whilst doctors and vets cared for people and animals. For a short time, the lot of the two groups improved but then famine struck and a downward spiral set in, which the students were unable to reverse. For all the well-meant intentions, the people of Tanaland ended up being worse off than before. Today, the effects of over hasty measures can be seen everywhere and instead of thinking that our mobility problems can be solved by the introduction of e-cars, Göpel argues that it would be better if people did not have to commute in the first place. This is the credo of Anne Hidalgo, Mayor of Paris, whose vision is that Parisians should have everything they need within a 15 minutes walk or cycle ride. To this effect she is having 40,000 flats built and is reclaiming a further 30,000 from Airbnb and other such platforms so that Paris can once again be where Parisians live. To improve the quality of life, 170,000 trees are to be planted. Time magazine has proclaimed Hidago as one of the 100 most influential personalities and Paris declared one of the world’s most interesting places when it comes to ecological and socially orientated planning. From this and other examples, Göpel extracts a methodology by which “transformation by design” may be achieved. This begins with understanding a problem through the acquisition of system knowledge. Then a goal is identified and a mission is formulated, such as Hidago’s “15-Minute City”. The third stage is the acquisition of a portfolio of relevant strategies through trial and error. Only then, in the fourth phase, are successful solutions incorporated into procedures and become strategy.

For Göpel, digital technology is either good or bad depending on how it is used and here she is deeply critical of the economy of attention has transformed the internet from being a platform where goods and knowledge were exchanged into a form of magic mirror that, drawing on the human need for acceptance and recognition among peers, has made millions of people addicted to social media, causing them to give up both their personal data and encouraging them to lose any ability to think independently and critically for themselves. She thus agrees wholeheartedly with the concerns voiced by Maryanne Wolf. Like Philipp Blom, Göpel recognises the immense power of narratives in our lives and on our ways of thinking and argues for a deconstruction of the narratives that underlie consumer culture. Modernism is very much associated with myths of the city and Göpel points out that modern cities erode our feelings of space and time and cause us to lose connection not only with people but also with the basic realities of life. What we need she argues, are not the narratives of loss, alienation and dislocation that contemporary culture supplies in abundance and relishes in but rather “a big reconnect”, in which purpose and the meaning of life once again become central. Focusing these thoughts at the end of We can do Better, Göpel draws on the Stoic concept of arete, which means “virtue” but with the implication that one should always do one’s best and strive to be the best that one can be. For the Stoics, the relation of a person with their inner self, or inner demon (daimon), was essential to the leading of a good and happy life and the Stoic conception of happiness, eudaimonia, means literally “a happy (inner) demon”. This is in accord with the view of the self advocated by Alain de Botton and it is important to emphasise that the inner demon by no means ignores the outside world, so that “being the best one can be”, includes the outside world and involves a rising to the challenges posed by it as well as the thankful acceptance of the gifts that it offers. Arete is thus an attitude in which we endeavour to keep our actions in tune with our intentions – articulated by the inner demon of the self and its conscience. It is in this context that Göpel’s notion of a „Happ“ is to be seen, with is the taking up and maintaining of dialogues with others being a part of the striving for arete, making the striving a dynamic process that, as shared, becomes communal and so acquires the capacity to be transforming.

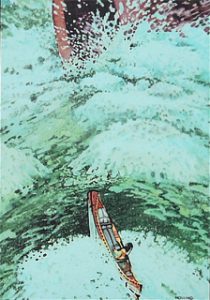

Taking a cue from Peter and Paul Lake, the story of Paddle to the Sea provides an example of how the merest seed of an idea can inspire a chain of people, none of whom know each other but all of whom help in bringing an endeavour to a successful conclusion.

The story begins when a boy at the top of Lake Superior carves a mode of an Indian in a canoe. Fitting the boat with a lead keel so that it will always float upright, he then carves a message on the bottom: „Please put me back in water, I am Paddle-to-the-Sea“. Then he leaves the model in the snow on the top of a slope that faces towards the Lake. When the spring comes, the snow melts and Paddle-to-the-Sea starts out on an epic journey.

Along the way he encounters danger, becomes damaged and is helped by a memorable cast of characters. In effect, each person in Holling C. Holling’s classic children’s story of 1941, acts in accordance with the principle of arete, giving what they can because they see it as being the the right and noble thing to do.