Philipp Blom is a historian whose books cover history, philosophy and politics but also include a number of novels. Working as a journalist, Blom has written for a wide range of quality English and German newspapers. Growing up in Germany, Blom studied philosophy, history and Jewish studies in Vienna and Oxford, completing his studies with a doctoral work on nationalism. After several years of living in London, he moved to Paris in 2001 and six years later, from there moved to Vienna. Apart from writing he also gives lectures and has curatored a number of exhibitions. At Symposium Dürnstein: Politics, Religion & Philosophy that, prior to the Corona pandemic was held every year in the town’s Augustinian monastery, Blom gave the 2018 opening lecture.

A year and a half later, also in the town’s Baroque monastery, he gave a lecture that was part of the celebrations held to mark the 25th anniversary of the Wachau being awarded UNESCO World Heritage status.

A year and a half later, also in the town’s Baroque monastery, he gave a lecture that was part of the celebrations held to mark the 25th anniversary of the Wachau being awarded UNESCO World Heritage status.

In his writing, he combines history and philosophy and uses essayist, literary techniques to bring his subjects to life. His book Nature’s Mutiny deals with the Little Ice Age that set in at the end of the Renaissance and endured until the end of the eighteenth century.

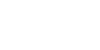

Frost Fair Held on the Thames at the beginning of the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age he argues, was a major factor in prompting Europe to move away from a Medieval economy and way of doing things, towards a more dynamic, capitalist way of life. The poor harvests frequently suffered, were he suggests, also the ultimate cause for the witch hunts and burnings that were carried out during the first half of the period under discussion. Only very slowly he points out, was a scientific approach and way of looking at the world adopted and only step by step were new methods of farming introduced that were capable of countering the effects of the colder climate.

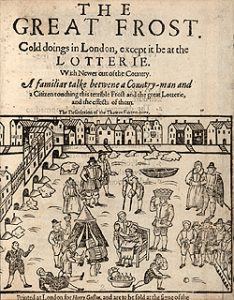

Frost Fair Held on the Thames towards the end of the Little Ice Age

Ultimately, this resulted in higher yields than had been achieved before the Little Ice Age set in. Combined with the increasing costs of fighting wars with modern weaponry, the Little Ice Age lead to the birth of the modern age with societies in which the GNP (Gross National Product) of a country became important and was identified as something that was desirable. Like other forms of agriculture, wine-growing was adversely affected, with yields slumping and grapes not always attaining the required degree of sweetness. As a somewhat paradoxical consequence, although less wine was being produced, in Krems and Stein, without exception, the town’s cellars were significantly enlarged. Instead of narrow passages, large vaulted spaces were created. This was so that the wine that was produced could be kept for longer. Storing the wine for longer it was found, helped reduce the dry and bitter tastes. In the case of the Dominican Monastry in Krems, where during the Middle Agges, the monks had made and stored their wine on the ground floor, with the advent of the Little Ice Age, they too found they needed more storage space and an extensive system of cellars, dating from this time was dug out under the monastry.

The „Mustard Room“ of Museum Krems diplayed in one of the vaulted cellars of the Dominican Monastry

The Little Ice Age also lead to a new kind of mustard being invented of in Krems, this being a way of processing the increased amounts of vinegar that were being produced as grapes repeatedly failied to achieve the required degree of sweetness. After four hundred years of producing its own mustard, the mustard known as Kremser Senf is now only made in Vienna and is exported all over the world.

Once praised by an abbot during the Middle Ages as the embellishment and renown of any table, from 1740-1850, the sour wine was also used as a raw material in the producton of a white lead pigment known as Kremser Weiß. Historians have long seen the down turn in the quality of wine being produced in Krems as a result of the Thirty Years War and the ecconomic decline that set in when, following the town’s forced return to Catholism, those who were not prepared to renounce the Protestant Faith were left with no choice but to move away. Blom’s thesis however intergrates this regional trend into a wider picture and explains why it was only in the Nineteenth Century that Krems was once again able to produce quality wine.

Once praised by an abbot during the Middle Ages as the embellishment and renown of any table, from 1740-1850, the sour wine was also used as a raw material in the producton of a white lead pigment known as Kremser Weiß. Historians have long seen the down turn in the quality of wine being produced in Krems as a result of the Thirty Years War and the ecconomic decline that set in when, following the town’s forced return to Catholism, those who were not prepared to renounce the Protestant Faith were left with no choice but to move away. Blom’s thesis however intergrates this regional trend into a wider picture and explains why it was only in the Nineteenth Century that Krems was once again able to produce quality wine.

Earthenware vessel for storing vinegar found at the Steinerlandstraße 118

Throughout Nature’s Mutiny, there are echoes with our own age and the problem of global warming. Accordingly, the book ends with a summarisation of climate change in our own era and in Blom’s next book, What is at Stake, the issue is given the in-depth treatment that it deserves. For Blom, the central truth of a culture is something that is transcendent and something that people of that culture “buy into”. In the Roman Empire, any country could agree to become a part of the empire. Though it lost its sovereignty, the country concerned gained the protection of the Roman army along with the possibility that roads and aqueducts might be built and trading opportunities and prosperity enhanced. Becoming Roman citizens, individuals too, could personally buy into a new way of life. With Christianity a similar deal is made and by believing in Christ and endeavouring to follow the commandments and the instructions of the parables, an individual can buy into the promise of eternal life. As the eternal life promised is abstract, art is used as a means of offering glimpses of what is to come. Following Blom, in consumerism too, a similar promise is made and provided one is prepared to work and earns one’s way in the world, one can buy into the consumerist dreams promised by advertising. Men are promised that with the right after-shave they will be transformed into heroes whilst women are persuaded that with the right beauty products they will become as alluring as Aphrodite. Here, as in Christianity, an important aspect of the buying in, is that that which is bought into, is transcendent and the promise promised is one of partaking in something that is “higher” in that it is over and above oneself. Thus branding and image become ever more important in order to create and sustain the beyond aspect of what is, with money, literally bought into. The problem with consumerism however, is that the more often one consumes, the more the experience of transcending one’s self through bought products begins to weaken. Just as a good Christian must try to be good every day, so too the consumer must repeatedly consume and want new things in order to keep the dream of heaven on earth alive. Thus we carry on consuming whilst all the time, an incipient nihlism eats away at us, destroying our faith that things can be changed for the better. Though we lose faith, we have no choice but to continue buying and this fits perfectly with societies whose aim is to continually increase their GNP, this requiring hungry markets of consumers who clamour for ever more products. In this way, global and national systems emerge which are dependent on perpetual growth. Although the negative effects on the environment can hardly be overlooked and have the potential to lead to a collapse of civilisation and quite possibly to our own extinction, nobody wishes to address the problem just now. This leads to consumer societies striving to exist in a perpetually sustained present that, following Blom, can only be described as “infantile”. Although at every turn, attempts at engineering an escape from this situation appear thwarted, Blom points out that the very mechanism of transcendence can also be used to save us and instead of buying into consumerist dreams we can buy into the dream of a sustainable future with green energy, less waste, less greed and less broken, hopelessly unrealistic dreams. As with the Christian faith, each step taken in the right direction constitutes a step toward the transcendent goal of perpetuating a scientifically orientated and environmentally aware culture. Becoming more aware of our surroundings, although we travel less and indulge in less pointless consumerism, our lives become enriched through our understanding and our playing a very real part in the attainment of a dream, the dream that one day there might really be peace and understanding on Earth. In striving towards this end, each piece of scientific knowledge that helps us along the way and which we understand, even if only partially, constitutes a temporary glimpse of the nature of the transcendent ideal striven for. Science and knowledge thus become reinstated as things that are desirable in themselves as glimpses of something that lies over and above us. In as far as our understanding has practical applications, it is to care for and preserve the world and its ecosystems of which we are a part and on which we, along with millions of other creatures, depend. It is Blom’s notion of transcendence and identification of the potential for transforming consumer transcendence into environmental transcendence that makes What is at Stake hugely important. Like de Botton’s Religion for Atheists, this is essential reading.